Spencer Henry WALKLATE

Spencer Henry WALKLATE

aka Spence

Late of Bondi Junction

New South Wales Police Force

Regd. # ????

Rank: Constable

Stations: Regent St – # 2 Division,

Service: From 3 July 1940 to 16 December 1943 ( Resigned to join Army in WWII ) = 3+ years Service

[blockquote]

World War II

Australian Imperial Force ‘Z’ Special Unit from 4 August 1944 Group ‘C’. Involved in Operation Copper.

Regiment: 33rd Militia Battalion

Enlisted: at Gunnedah

Service # NX202843

Rank: Lance Corporal

Embarkation: 21 February 1945 for Papua & New Guinea

Next of kin: Linda Maude O’Keefe – wife

Religion: Methodist

Single / Married: Married

Returned to Australia: No. K.I.A.

[/blockquote]

Awards: No find on It’s An Honour

Born: 11 January 1918 at Brushgrove, Clarence River, near Maclean, NSW

Died on: Between April – June 1945

Age: 27

Cause: Executed ( beheaded ) by OAWAGA Waichi – Japanese Petty Officer

Event location: ?

Event date: ? Between April – June 1945 ( WWII )

Funeral date: ? ? ?

Funeral location: ?

Buried at: Muschu Island, Papua & New Guinea

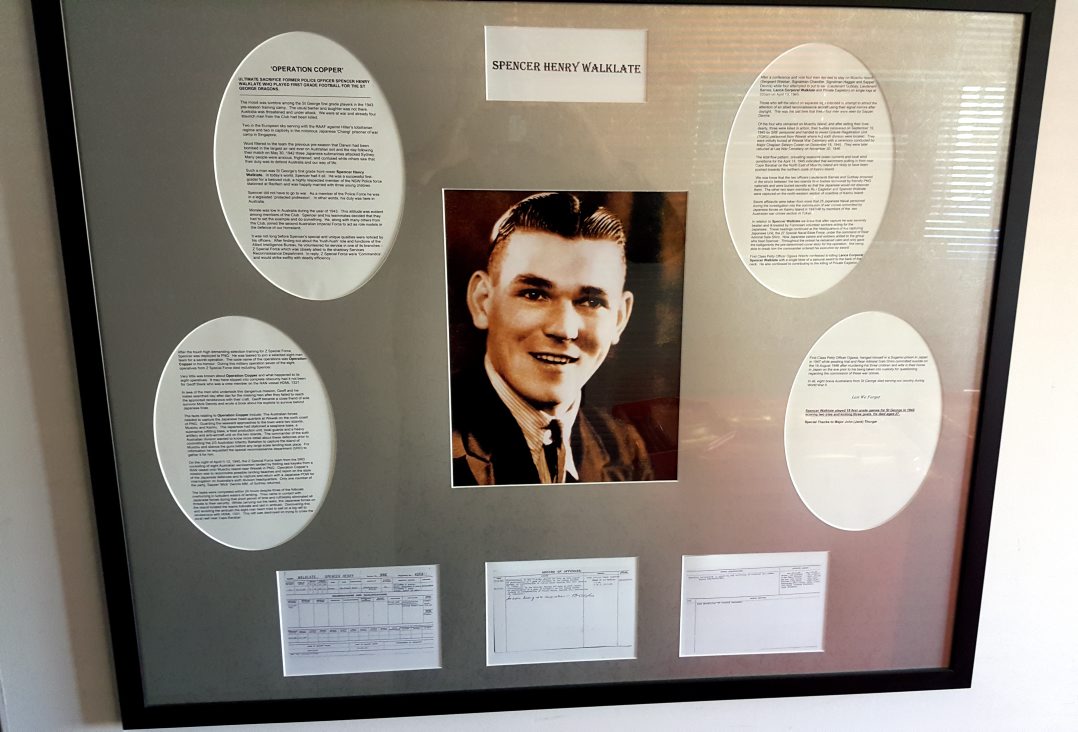

Memorial located at: St George Police Station has a conference room named the ‘ Spencer Henry Walklate ‘ room, named in honour and memory of the man.

A plaque and story is on display at the Police Station, 13 Montgomery St, Kogarah.

The room was named by the, then Commander, Peter J O’Brien, APM.

[alert_yellow]SPENCER is NOT mentioned on the Police Wall of Remembrance[/alert_yellow] *NEED MORE INFO

[divider_dotted]

FURTHER INFORMATION IS NEEDED ABOUT THIS PERSON, THEIR LIFE, THEIR CAREER AND THEIR DEATH.

PLEASE SEND PHOTOS AND INFORMATION TO Cal

[divider_dotted]

May they forever Rest In Peace

[divider_dotted]

Spencer Henry Walklate conference room

[divider_dotted]

Operation Copper

Concerning the murder of NSW Police Constable Spencer Henry Walklate and others – Muschu Island in the Japanese occupied Territory of Papua & New Guinea – April 1945.

by Detective Senior Sergeant Garry Nowlan

On the 150th anniversary of the NSW Police Force many former and retired Police Officers who have contributed so richly to our history have been remembered. However, we rarely mention the achievements of Police Officers in times of war. Many NSW Police Officers have served during many wars, deployments and peacekeeping operations over many years and some have paid the supreme sacrifice.

This is the story of one of them.

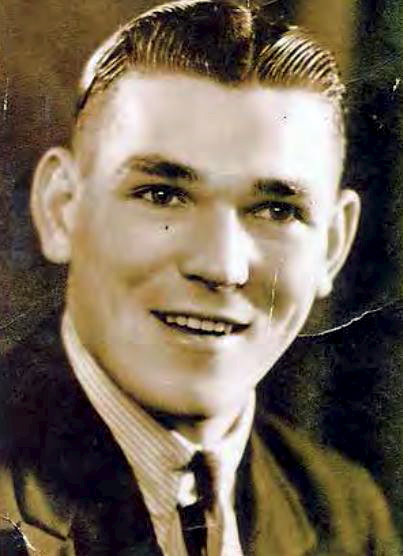

Spencer Henry Walklate was born at Brushgrove on the Clarence River near Maclean in northern NSW on the 11th January 1918. He was enrolled and educated at the nearby Wardell Public School in 1923. Spencer attended Church, Methodist Sunday School and was a fit and healthy country kid who excelled at sport. After leaving school he became a grocery salesman and purveyor of small- goods. He later met a Grenfell girl named Linda Maude O’Keefe who was to become the love of his life. They married at Gunnedah on the 31 January 1938 and settled down to start a family.

But, these were uncertain times and war clouds gathered over Europe. A fragile peace had existed with Germany since the end of WW1 but that was shattered when Hitler invaded Poland in 1939. When Britain declared war on Germany and her allies Australia and all the other Commonwealth Nations also went to war. Many young Australian men went off to fight in Europe the Middle East and North Africa.

Life was good in quiet country NSW for a young man with a new wife and a bright future. However, due to events abroad, Spencer became unsettled and through a strong sense of duty to country, joined the 33rd Militia Battalion at Gunnedah, where he underwent basic military training.

Meanwhile, Japan watched events in Europe unfold with interest. Japan had until the 19th century been a very

isolationist society with little contact from the outside world.

Then, in 1860 Japan formed an unlikely but long standing cultural and intellectual association with Germany. But, due to conflicting political aspirations over China, Japan declared war on Germany and fought on the British side during WW1. An uneasy peace existed for the next decade or so but in 1931 Japan invaded Manchuria and fought a long and bloody war against China, committing many atrocities.

The conflict expanded Japanese military power in the region and it’s troops soon became battle hardened, experienced combat veterans. By the mid 1930’s a rising Japan had formed a strong military alliance with an increasingly aggressive Germany and became part of the Axis Alliance along with Mussolini’s Fascist Italy. The ultimate aim of this pact was world domination.

On observing Hitler’s early successes in Europe, Japan a small country with limited resources, cast it’s eyes south.

To the rich resources of land, agriculture, oil, rubber, iron ore and coal. And their aspirations turned to South East Asia, and beyond. The U.S. had remained neutral for the first 2 years of WW2 but they had a powerful naval presence in the pacific based at Pearl Harbour, which threatened Japanese ambitions. So, on 7 December 1941 the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour to destroy the U.S. Pacific Fleet.

Simultaneously and through a series of coordinated, vicious attacks Japan invaded the Philippines, and moved quickly south through Indo-China taking Burma,

Thailand, Vietnam and Malaya. Fortress Singapore fell on 15 February 1942 after one week of bitter fighting and 130,000 Commonwealth troops

entered the hell of Japanese captivity.

This included over 22,000 Australian troops mainly from the 8th Division.

Just 4 days later on 19 February 1942 Darwin was bombed by a massive Japanese force destroying much of the town and many Allied ships in Darwin Harbour. The attack was carried out by the same bomber group which attacked Pearl Harbour, however more bombs were dropped on Darwin than at Pearl Harbour. Australia would be attacked and bombed by the Japanese on 63 occasions. This was followed up with the raid in Sydney harbour on 31 May 1942 by 3 midget Japanese submarines. Sydney and Newcastle were shelled by Japanese submarines and Allied shipping was sunk off the eastern coast of Australia.

The Japanese invaded Rabaul massacring 130 Australian POW’s at Tol Plantation and began building an airfield on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands to provide a base from which to further isolate and attack Australia. By July 1942 the Japanese occupied the Mandated Territory of Papua & New Guinea, Timor, Nauru, and the Solomon Islands and also held many other islands just to our north.

These were the darkest days for Australia and the Japanese advance south seemed unstoppable. Due to the imminent threat to Australia, Prime Minister Curtin defied Winston Churchill and brought Australian troops home from the Middle East and North Africa to defend Australia. The battle on the Kokoda Track was still raging, when in September 1942 Japanese land forces were for the first time stopped and defeated by Australian troops at the battle of Milne Bay. The tide had turned. Then the slow and painful slog through mud, swamp and jungle began, to push the Japanese back. To borrow the words of Winston Churchill, “This was not the end. It was not even the beginning of the end. But it was the end of the beginning.” It looked for the first time like the Battle for Australia could be won.

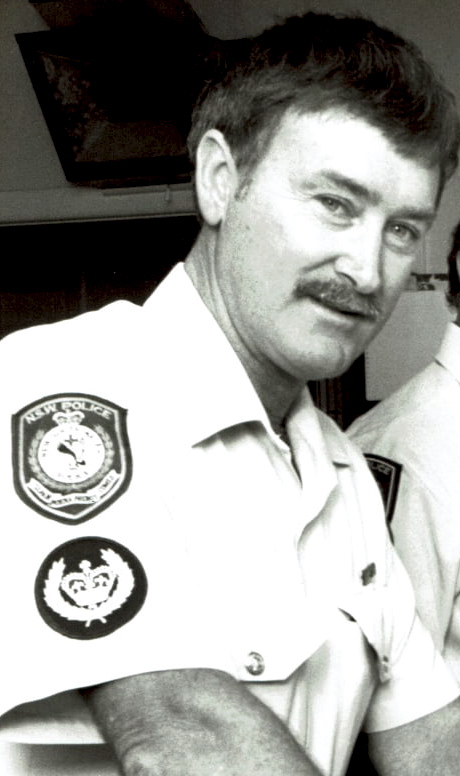

Meanwhile, Spencer Walklate observed events from afar. He had decided to move closer to the action and he and Linda left the bush and moved to Sydney taking up residence at Bondi Junction. Again through a sense of duty he decided to join the NSW Police Force at the age of 22 years so he could do his bit to defend the homeland. He joined the NSW Police Force on 3rd July 1940 and after initial training at the Burke Street Police Academy Redfern, was posted as a Probationary Constable to No 2 Division Regent Street. He performed wartime General Duties and was no doubt disturbed by world events, particularly the Darwin air raids and Japanese Submarine attacks on Sydney Harbour.

Spencer had developed into a fine, solidly built, very large and physically fit young man.

In addition to his demanding role as Constable of Police pounding the beat around Central Railway Station, Broadway and Paddy’s Market, he had developed into a first class footballer. He joined St. George Football Club and in 1943 played 15 first grade games as a forward scoring 2 tries and 3 goals. He was also a strong swimmer and in his spare time was a Bondi Surf Life Saver. Spencer Walklate was a big man of many talents. Just the kind of man you might need when your country was fighting for it’s very existence In June 1942 the Australian Military formed a Special Forces unit for clandestine commando operations behind enemy lines. Their main role was reconnaissance, intelligence gathering, sabotage and supporting resistance efforts in occupied territories. It was a secret force named

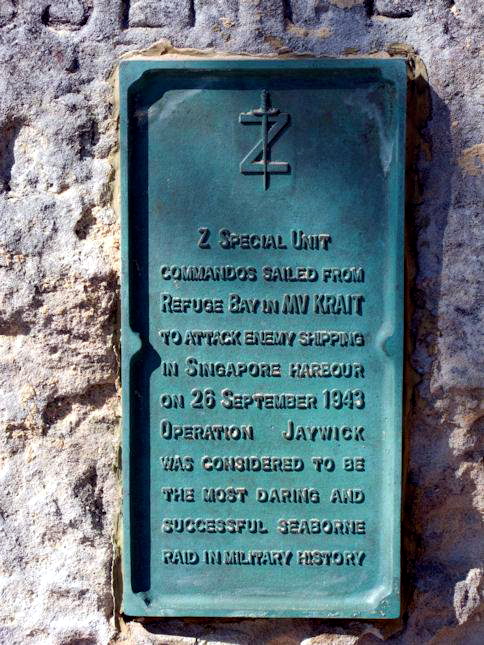

simply ‘Z’ Special Unit. The unit was administered through Special Operations Executive (SOE) Australia and was made up entirely of volunteers. It’s recruits came from various army and naval units who volunteered for ‘Special’ service in extremely high risk and dangerous operation’s.

They trained in a variety of secret training camps including Camp Z in Broken Bay, Z Experimental Station in Cairns and there was a commando school on Fraser Island. In June 1943 a ‘Z’ Special Unit commando team based on Magnetic Island staged a mock raid in Townsville Harbour by placing dummy limpet mines on allied shipping. When the mines were discovered it caused a furore as the navy thought the mines were real. The commander of the unit was arrested and subject to disciplinary action. But, the lessons learned here were later used in the highly successful Operation Jaywick raid by ‘Z’ Special Unit in Singapore Harbour, where 39,000 tons of enemy shipping was destroyed by limpet mines.

By late 1943 Constable Walklate was in a state of personal crisis. He did not want to leave his young wife or his job, but could find no other option.

His country was at war and he had army training. He knew men who were going off to fight. Not to go was unthinkable.

At the time the Police Force was designated a reserved occupation. Police were not permitted to join the military forces as it was deemed just as important for them to remain at home to keep the peace, defend the homeland and protect critical infrastructure. But, as so many Police were resigning to enlist, the rule was later relaxed and Police were allowed to enlist and return to the Force at the end of their military deployment.

So, Spencer made the only decision he could. In order to enlist he resigned from the NSW Police Force on 16th December 1943 and joined the AIF at Paddington on 31 December. On 5 January 1944 Spencer Henry Walklate Serial No NX202843 marched into 3rd Australian Army Recruit Training Battalion. He was 25 years of age.

Private Walklate‘s Police Training and leadership abilities held him in good stead and 3 months later he was promoted to Lance Corporal on 16 April. On 16 July 1944 Lance Corporal Walklate attended and successfully completed the jungle warfare course at the Australian Jungle Warfare Training Centre, Canungra. But, as in peacetime Spencer Walklate excelled and wanted to be among the best. So, on 4 August he volunteered for, and was accepted into ‘Z’ Special Unit. As this was a highly specialised unit he had to accept reduction to the rank of Private. But, after gaining all his skills and proficiency levels on 29 October 1944 his rank was reinstated to Lance Corporal.

Due to the level of secrecy involved, not much is known of his service over the next four months however it is highly likely he attended one or more of the ‘Z’ Special Unit training camps for specialised training in espionage and battle survival techniques. He departed Australia in secrecy for war service in the occupied Territory of Papua & New Guinea on 21 February 1945. He did not know he would never see Australia or his beloved wife Linda again.

Lance Corporal Spencer Walklate was posted to Group ‘C’ – ‘Z’ Special Unit in Lae where he trained in secret with other members of the group. It is not known what Spencer Walklate did or where he went for the next several weeks.

But, what is known is that he was about to enter the history books as taking part in one of the boldest, most heroic and tragic commando raids behind enemy lines in the South West Pacific theatre of war. Operation Copper.

Of course the name is a mere co-incidence, but the irony is not lost on the astute reader.

By April 1945 the allies were well and truly winning the war. In Europe the Russians were advancing on Berlin and Hitler would commit suicide within weeks. The Japanese had lost the war but were in denial and were being pushed back to Japan or decimated island by island. General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Allied Commander in the South West Pacific, was island hopping eager to complete his self fulfilling prophesy of, “I shall return” to the Philippines. And he did not care how many Australians had to die in order for him to fulfil it. As the Japanese had already proved they would rather die than surrender, the Americans were by-passing Japanese held islands in their rush north. MacArthur, determined to have all the glory for America had relegated the Australian troops, who were

the first to ever stop the Japanese and who had done the lion’s share of the fighting in New Guinea, to clearing up the stranded Japanese remnants. But, this was no easy task as the Japanese had been on some of these islands for years. They had established strong defences and built food gardens to enable them to survive and were willing to fight to the death to hold their ground.

And so it was that plans were made for an Australian invasion of Wewak on the north coast of New Guinea where the Japanese were stranded in strength, with nowhere else to go. Many diggers after the war would say that many a good man was lost and most of these operations were unnecessary as the Japanese could have just been left to starve and ‘wither on the vine’.

Intelligence reports indicated that there were two big 140mm naval guns situated on Muschu Island which commanded the coastline where the invasion was to take place and could wreak havoc on Australian invasion troops and shipping. Muschu was a small nondescript tropical island, like thousands of other small tropical islands, situated just 4kms off the coast near Wewak. Surrounded by coral reefs it was flat around the fringes, with scattered rocky coves, spectacular lagoons and beaches. It was hilly in the middle with a couple of isolated native villages and covered in dense tropical jungle. It was also the home for 700 very hostile Japanese soldiers. ‘Z’ Special Unit and Lance Corporal Spencer Walklate, were given the task of locating and disabling the guns on Muschu Island.

The following members of the Group ‘C’ – ‘Z’ Special Unit raiding party were assembled and briefed at Aitape on 8 April 1945:

Lt. Thomas Barnes, Lt. Alan Gubbay, Sergeant Max Weber, Signalman Michael Hagger, Private John Chandler, Private Ron Eagleton, Sapper Edward ‘Mick’ Dennis and Lance Corporal Spencer Henry Walklate.

‘Mick’ Dennis and ‘Spence’ Walklate had already become best mates and both had close familial connections with the NSW Police Force. ‘Mick‘ had been an unarmed combat instructor with the NSW Police Force before the war. His sister, Clare Dennis, was a 1932 Olympic 200 metre breaststroke swimming Gold Medallist, who was married to George Golding, a NSW Police Detective and 1930 Empire Games track and field Bronze Medallist. His father Alexander Dennis was a Police Prosecutor in the NSW Police Force at Burwood.

During the Aitape briefing the team was provided with maps, prismatic compasses, aerial photographs, secret wireless codes and intelligence reports on their area of operations. They would be inserted into the area by Naval Patrol Boat and would then paddle to the island by folding canvas kyak-like boats called ‘folboats’. Each man carried a 9mm automatic Sten SMG backed up by a .38 calibre Smith and Wesson Model 10 revolver. The raiding party was also issued with three 9mm ‘Welrods’ which were a silenced bolt action repeating pistol also known as ‘The Assassins Gun’. Other equipment included the Fairbairn Sykes commando fighting knife, two radio transmitters, walkie talkies, Very lights (flares), signal mirrors and rations for 24 hours. The mission was simple. Get in, capture a

Japanese prisoner for interrogation, find the guns, disable them if possible, contact the naval patrol boat by wireless and get out.

The night of 11 April 1945 was selected as it was a dark, moonless night with favourable tides. That afternoon the raiding party boarded Harbour Defence Motor Launch (HDML) 1231 at Aitape and was conveyed under cover of darkness on the 8 hour, 150 kms journey to within 5 kms of Muschu Island. At 2130 hrs they disembarked the patrol boat in four folboats, two men paddling in each and set off into enemy held territory. And into the lion’s den.

As the men’s night vision kicked in all eyes strained on the dark brooding mass ahead. The only sight that pierced the darkness was the luminous trail left in the rippling wake of the boats as they carved their way through the calm tropical waters. The only sound that broke the silence was the dip of paddles as they sliced the still black water, the slap of the waves against the flimsy canvas hulls of the tiny boats, and the faintly suppressed groans of straining men as they pulled the fragile craft closer. The eerie blackness was occasionally violated by the phosphorescent flash made by some unseen creature lurking in the murky depths below

the sweating, determined men. On they went through the still, balmy, tropical night towards the dark foreboding shadow of the unseen enemy’s lair.

Then disaster struck. At 2230 hrs the folboats hit an uncharted reef and capsized. The party managed to recover the boats but much of the party’s weapons and

equipment was saturated or lost in the black churning water. Two hours later 8 tired, wet and bedraggled men dragged themselves to shore where the party slept fitfully 15 metres inland.

At 0500 hrs on 12 April they stood to. Weapons at the ready clutched in tense, sweating hands, eyes straining through the thick jungle foliage and ears fine-tuned to pick up the slightest hostile sound. When no enemy activity was detected they concealed the boats 50 metres inland in dense undergrowth and set up a base camp some 100 metres further inland where the wireless transmitter and equipment was concealed.

The team then moved east for 30 minutes where they located two well oiled Juki machine guns in firing positions covering the beach. They dismantled the guns and threw them into the sea. The party continued across the island and found strong enemy posts every 50 metres along the coast with a network of trenches and connecting tracks behind. A further four machine guns were located and dismantled. A food garden and some enemy occupied huts were located. There were some bomb craters in this area and here they obtained fresh rain water for the first time.

That afternoon they captured a Japanese soldier who was bound and gagged.

They then tried to find their way back to their base camp but got lost. Taking the wrong track they came upon a Japanese camp. They diverted around the camp and on some cliffs found several gun positions.

They made contact with two Japanese near some huts and both were shot dead with the silenced ‘Welrods’.

They then moved back east and finally found the naval gun positions they were looking for. Grid references were taken so the guns could be destroyed by allied aircraft and with the mission nearly accomplished they began to make their way back to base camp.

But, again disaster struck. As they passed near a Japanese patrol the prisoner slipped his gag and called out alerting the enemy. The prisoner was immediately shot and the party went to ground. There was a strong Japanese presence on the island and by now they were alerted to the presence of the raiders and several hundred Japanese were out in force searching for the Australians. That evening they moved back to the folboats but found they had been discovered by the Japanese and an ambush had been set nearby with a machine gun covering the boats. The party then withdrew, made a fresh base camp and now with no wireless transmitters had to plan their getaway.

They decided to try for the mainland so constructed a raft from logs and at 2000 hrs put to sea but the raft smashed to pieces on a coral reef. This time they lost the remainder of their weapons and equipment and the only man to retain his weapon and pack was Sapper Dennis. It would save his life and enable him to live to tell the story of what happened next.

They returned to the island and after much debate decided by democratic vote to break up into two groups. One group of four men being Sergeant Weber, Private Chandler, Signalman Hagger and Sapper Dennis, favoured remaining on the island and would try to recover a wireless transmitter to contact the rescue boat. The other group comprising Lt Barnes, Lt Gubbay, Private Eagleton and Lance Corporal Spencer Walklate, favoured putting to sea on separate logs to try to make it to nearby Kairiru Island and signal patrolling allied reconnaissance aircraft with mirrors. The men said their goodbyes, shook hands and wished each other luck.

Spencer Walklate and his party then set to sea and the last time he or his mates were seen alive by friendly eyes was as they paddled quietly off into the darkness. Four tiny, bedraggled figures bobbing along on coconut logs carried on the unpredictable currents of the Solomon Sea. Into the vast, enemy held, shark infested unknown.

The story of what happened to Spencer Walklate and his mates cannot be told without reference to the extraordinary tale of survival by Sapper Dennis. The Dennis party moved inland and rested. They spent the 13/14 April observing the movements of the Japanese and watching for signals.

At 0600 hrs on 15 April they moved back to their original base and recovered one of the wireless transmitters. While moving back to a safe position to set up the radio they were ambushed by a Japanese patrol. Sapper Dennis shot two Japanese with his sten gun and the party split up discarding the wireless set in the scrub. Dennis was unable to locate the rest of the party throughout the day. He returned to the bomb crater to get fresh water but found it sour and bitter to the taste. The Japanese were poisoning the water holes to deny the intruders water. Dennis then moved west and in an encounter near a hut shot one Japanese. He then surprised a Japanese Patrol of four and shot one wounding several others. He hid for the night in the scrub and heard Japanese patrols moving around and heard shots near the beach.

Having given up hope of finding the rest of the party he continued west and found a Japanese machine gun in position but unattended so he toppled it over a cliff. He slept in a sago forest and could hear and see the Japanese searching for him. As per mission objectives he continued to record the details and grid references of all Japanese positions, strengths and infrastructure in his note book.

On 16 April he reached the west coast of the island near Muschu Bay and decided to try for the mainland. He found a suitable plank on a wrecked Japanese barge and hid it.

He remained in the area until night and returning to the plank found it had been removed back to the barge. He retrieved the plank and then paddled for 10 hours through shark infested waters and battled strong ocean currents until making the mainland two hours before dawn. He rested, then on 17 April set off north west towards what he hoped were the Australian lines. He evaded Japanese patrols but was observed by two Japanese and shot one.

He later encountered another four man Japanese patrol and shot two. He then surprised two Japanese but his SMG misfired.

The Japanese were so frightened one lost his rifle and they both ran away.

He continued west for 20 kms through enemy territory until 1400 hrs on 20 April when he contacted a patrol of the 2/7th Australian Commando Company. His ordeal was over and the details of his intelligence debrief conducted at Aitape on 21 April 1945 form the basis for this narrative.

Sapper ‘Mick’ Dennis, former NSW Police unarmed combat instructor, was awarded the Military Medal for this extraordinary feat of courage and endurance.

But what of the other 7 men of Operation Copper?

The war ended just 4 months later with the dropping of the atomic bombs ‘Little Boy’ and ‘Fat Man’ at Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6th and 9th August 1945 respectively. After cessation of hostilities the Australian military commenced it’s War Crimes investigations and trials into Japanese atrocities. Muschu Island was converted to an internment camp for Japanese POW’s and Japanese officers and soldiers were interviewed to establish what happened to missing allied servicemen and women. But, the Japanese were often untruthful, uncooperative and sought to cover up the truth for fear of being tried and executed as war criminals. It had been a long and bloody war and most Allied Governments just wanted to forget about it. The Americans were even less enthusiastic to pursue high level war criminals as General MacArthur was given the task to re build post-war Japan and he used high ranking Japanese officers and officials, many of whom were war criminals, in the process. So, many war criminals escaped justice, as was to be the case for the missing men of Operation Copper.

In 1945/46 war crimes investigators interviewed senior Japanese officers on Muschu Island re the fate of the Operation Copper men. They were told that the three men from the Dennis party were ambushed and killed while trying to operate a radio set. However, natives had reported seeing the mutilated bodies of these men on Muschu in April 1945. While the Japanese claimed the bodies had been damaged by artillery shells, Sapper Dennis has always disagreed with this. He believes his three mates were captured, tortured and murdered by the Japanese.

The mutilated bodies could indicate they were cannibalised which was a common practice by the Japanese in New Guinea during WW2. After the war the remains of the bodies of Sergeant Weber, Private Chandler and Signalman Hagger were recovered from a shallow grave and re-buried at Wewak. They were later exhumed and moved to Lae war cemetery. At least one body appeared to have been decapitated and another was shot through the head.

But what of Spencer Walklate and his 3 mates, who set off into the unknown so long ago on coconut logs?

The Australian Army concluded in 1946 the party was drowned at sea or taken by sharks. But, many years after the war, with the declassification of military documents, new information became available and has shed fresh light on what happened.

It is now known that natives on nearby Kairiru Island told military investigators that up to three Australian’s came ashore on Kairiru in April 1945 and were executed by the Japanese. The Japanese denied this claim stating that two airmen did come ashore but they died of sickness and disease two days later. The native claims were ignored and never followed up at the time.

But, recently Australian Army documents have surfaced containing eye witness accounts of the murder of two Australian soldiers on Kairiru Island, including an account by the Japanese officer who carried out the executions.

According to these primary source documents between April-June (sic) 1945 a very large Australian ‘airman’, perfectly fitting the description of Spencer Walklate, was captured on Kairiru. ‘Z’ Special Unit operatives would have used a cover story if captured as espionage was punishable by summary execution, while ordinary servicemen were entitled to protection under the Japanese Code of Military Law. (Japan was not a signatory to the Geneva Convention). So, claiming to be an airman shot down or crash landing in the vicinity made perfect sense.

It is also known that checks of military war dairies indicate that no Australian airmen were lost in that location at that time. The Australian POW referred to in this document is almost certainly Spencer Henry Walklate.

Following is the disturbing firsthand account of his beheading murder, sourced from official Australian Department of Army War Crimes Archives and extracts taken from an interview with Ensign OAWAGA Waichi of the Japanese Imperial Navy, who was stationed on Muschu Island in 1945.

OAWAGA Waichi (states): During the first part of June 1945, an Australian airman was brought to headquarters from the north coast. At about 1300 Medical Officer MARUYAMA came to the sick bay and I received the order:

“Petty Officer OAGAWA, execute him.”

Thereupon I went to the scene of the action. At a spot about 100 yards away in the direction of headquarters a large Australian airman, blindfolded and wearing Japanese summer clothing, was being held with his arms behind his back by a guard detail of the sixth squad. He was kneeling on both knees in front of a hole in the ground. I approached Ensign FUMIYA, the chief of the guards, and reported:

“I have come upon orders from the medical officer.”

“Hurry and execute him.” (HYAKU Kire) I was ordered, so I borrowed the sword from the NCO who had come for liaison purposes and decapitated (the prisoner). With only a single stroke of the sword, he fell forward and died.

At this time there were present from headquarters the Staff Engineer Officer, Secretary KAWADA, Medical Ensign OMOTEZAKA, Supervisor Petty Officer (medical) SUZUKI and Leading Seaman MACHI.

Besides these there were fifteen to twenty officers and guards.

The corpse was buried on the spot under the direction of Ensign FUMIY A.

The same grim, barbaric ritual was repeated 10 days later with the capture and murder of a second member of the Operation Copper party. However, the precise identity of this soldier is not known and he was heavily drugged with Narcopon (Opium) prior to execution.

OAWAGA Waichi (states): “ About ten days had passed since the first incident when again an Australian airman was brought to headquarters from the north coast. At about 1500 I received the order from the medical officer:

‘Execute him with an injection of one CC of Narcopon.’

Thereupon I took one CC hypodermic needle and one CC of narcopon from the dispensary and went to the scene of the action. Lt (s.g) AMENOMORI and Secretary KAWADA were investigating in the finance room.

A fatigue detail was digging a hole. In about two hours the investigation was finished and an Australian of average stature, blindfolded and wearing Japanese summer clothes, was lead out by the guards. His hands were held behind his back and he was made to kneel in front of the hole.

The medical officer ordered me:

‘Give him the injection’ (CHUSHA SHIRO), so I injected one CC of Narcopon into the lower part of the left shoulder blade. Then I borrowed a sword from Superior Petty Officer KAWANO. About fifteen to twenty minutes after the injection the order:

‘Execute him’ (KIRE) was given, so I raised the sword over my head and brought it down, decapitating (the prisoner).

The Australian fell forward and died. Under the direction of Ensign FUMIYA, the corpse was buried on the spot.”

It appears that possibly one other member of the Walklate party met a similar fate with the fourth probably lost at sea.

Surprisingly, no Japanese solder was ever charged with war crimes regarding the murders of the Operation Copper men, in spite of this compelling evidence. The information provided by Sapper Dennis, the sole survivor of the Operation Copper raid, was used in the planning for the successful invasion of Wewak and the subsequent defeat of the Japanese which ended the Japanese occupation in New Guinea.

And so ends the heroic but tragic story of the men of Operation Copper and of the murder of Spencer Henry Walklate. Athlete, elite sportsman, football star, surf life saver, soldier, commando, POW, war hero, loving husband and NSW Constable of Police. Executed without trial by war criminals, he lies in an unmarked grave, in a lonely foreign place, on a tiny god forsaken island no one has ever heard of.

Postscript:

Each ANZAC Day, Edward Thomas ‘Mick’ Dennis MM, rises early.

He polishes his shoes, dresses in his best suit and carefully pins the shining row of bronze and silver medals with their brightly coloured ribands on the left breast of his jacket just above the pocket. The RSL badge and Returned From Active Service badge complete the ritual. Then, arming himself with his walking cane, he shuffles off to the dawn service. Rain, hail or shine, he has done it dutifully for 69 years. At 96 it is getting harder, but he knows he has to go. As he stands for The Last Post, on weakened, shaky legs, he remembers. He remembers the happy, smiling, youthful faces of his mates. He remembers them just the way they were, then. As if frozen still in time. Their bodies not wasted by age or sickness or despair. They have become ageless. He remembers Muschu Island, his mate ‘Spence’ Walklate and what they did there so long ago. And for a brief moment he stiffens and somehow grows taller. A tear comes to his eye. He wipes it with his handkerchief and with head bowed, shuffles slowly off home.

Until next year.

In a final irony, the naval guns at Muschu Island were never fired in anger and remained silent during the campaign.

The Japanese commander was afraid if they were used the Allies would be alerted to their position and they would be destroyed by superior allied air power. They are still there today. Lest We Forget.

Reference List:

Dennis D.

(2006)

‘The Guns of Muschu’,

Allen & Unwin,

Sydney,

Australia.

www.gunsofmuschu.com

Australian National Archives.

Australian War Memorial Archives.

http://www.peacekeepers.asn.au/mag/2014winter/PKWinter14.pdf

[divider_dotted]