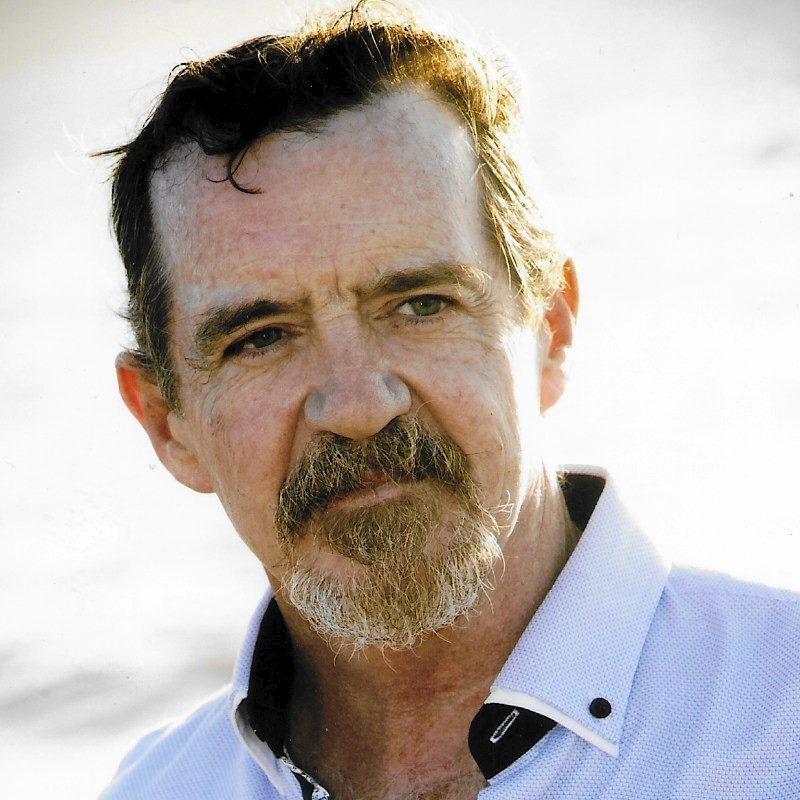

Peter James McGRATH

Peter James McGRATH

New South Wales Police Force

Member of Police Academy Class 227

Regd. # 23807

Rank: Probationary Constable – appointed 26 June 1987

Constable – appointed 26 June 1988

Detective Senior Constable – Death

Stations: Petersham ( 1987 ) – 11 Division, Annandale Police Station

Service: From Pre June 1987 to 15 June 1995 = 8+ years Service

Awards: ? Nil

Born: 11 April 1963

Died on: 15 June 1995

Cause: Suicide – jumped from 7th floor

Event location: Camperdown, NSW

Age: 32

Funeral date: ?

Funeral location:

Buried at: Cremated at Rookwood

At 4.15pm on 15 June, 1995 the senior constable fell to his death from a building in Glebe. He was off duty and on sick leave at the time. It was later determined that he was suffering from work related Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, depression and anxiety as a result of his policing experiences.

The senior constable was born in 1963 and joined the New South Wales Police Force on 26 June, 1987.

This member IS mentioned on the National Police Memorial Wall.

Death Of Detective Constable Peter McGrath

| About this Item | |

| Speakers | Gallacher The Hon Michael |

| Business | Adjournment, Condolence |

DEATH OF DETECTIVE CONSTABLE PETER McGRATH

The Hon. M. J. GALLACHER [4.49]: I bring to the attention of all honourable members yet another example of bureaucracy gone wrong. On 17 August 1992 Detective Constable Peter McGrath attended the scene of an armed robbery in progress at the Associazione Polysportiva Italo-Australiana club, the APIA club. Offenders were present and were armed. They had taken eight hostages and were in the process of collecting $60,000 from the armed robbery when the police arrived. It was a classic stand-off situation, with the offenders and police pointing loaded firearms at each other. The cool head of this officer and his partner resulted in both offenders eventually giving up. On 26 November 1992 Detective McGrath together with another officer whilst off duty were viciously attacked by approximately 12 males, resulting in serious injury to Detective McGrath’s companion and grave psychological illness to himself.

During the course of Detective McGrath’s duty he attended a domestic situation in which a mother and her de facto partner had placed a baby into a bath of boiling water before picking the skin off the baby and putting it to bed. The baby died a few months afterwards. Detective McGrath had to attend the post mortem. At the time of the trial of the offenders the detective’s wife had given birth to a son. In May 1993, as a result of the assault in November 1992, Detective McGrath began to show signs of depression, which were accepted by the Police Service as illness related to the course of his duty. His doctor supplied information to the Police Service regarding his illness and it was accepted that he had been hurt on duty.

By June 1995 Detective McGrath’s psychological condition had deteriorated. He believed that he was being followed by personnel from the Royal Commission into the New South Wales Police Service. He believed that he was going to be set up by police in relation to a crime. On 15 June 1995 he went to work at Annandale with the purpose of resigning. Detective McGrath’s supervisor realised that he was suffering from depression, talked him out of handing in his resignation and sent him home on annual leave. Later that afternoon Detective McGrath told his wife that he was going to resign. He left his home but instead of attending the police station he went to a high-rise block of flats in Camperdown and jumped to his death.

Contrary to rumours, Detective McGrath was not the subject of any royal commission inquiry, and I am in possession of correspondence to that effect from Mr Michael Finnane, QC, who represents the Police Service at the royal commission. Detective McGrath’s integrity is not in question. The Police Service and the people of New South Wales can ill afford to lose police of the calibre of Detective McGrath. I resigned from the Police Service and within three weeks received my superannuation payment. Detective McGrath died on 15 June 1995 but his wife did not receive his superannuation payment until August 1996 – 14 months after his death. On 26 June 1996 she received a letter from the Police Service telling her that his death was not as a result of his police work.

Detective McGrath has left a wife and two children, Kata aged four and David who is now two. His wife must go it alone without any support from the Police Service. I have written to the Commissioner of Police in regard to the appalling treatment that this woman has received and I look forward to hearing from him that the decision made earlier this year will be reversed. On 19 September 1996 Mrs McGrath personally filed an application for determination with the Compensation Court of New South Wales to challenge the decision of the Police Service so that she might be entitled to a pension. She has to pay for those proceedings herself. The money that Mrs McGrath is using is money from the family, money that would be better used for the children.

I do not believe that this case has been accorded the credit to which it is certainly entitled. The Commissioner of Police must immediately reinvestigate this matter to ensure that Mrs McGrath is treated justly. It is important that all wives and husbands and all children whose fathers and mothers work for the Police Service know that if they are unfortunate enough to lose their loved ones they will be protected. Psychological illness does not disbar an officer from consideration for compensation from the Police Service. I firmly believe that this matter is one that deserves just consideration and I hope that the Commissioner of Police accords it such consideration expeditiously.

Motion agreed to.

House adjourned at 4.53 p.m. until Tuesday, 29 October 1996, at 2.30 p.m.

http://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/prod/parlment/hansart.nsf/V3Key/LC19961024053

http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/holding-judgement/2007/06/08/1181089328815.html?page=fullpage

It took up 451 hearing days, heard from 902 public witnesses and cost an estimated $64 million. Malcolm Brown reports on the Wood royal commission, 10 years on.

It began on June 15, 1995, when an unnamed Annandale detective jumped to his death from the seventh floor of a building, apparently through fear of the Wood royal commission. The detective’s suicide was followed by those of Ray Jenkins, a dog trainer (July 10), and Inspector Robert Tait, the acting patrol commander at Narrabri ( March 29, 1996 ). Nineteen days later a former Wollongong alderman, Brian Tobin, gassed himself.

On May 8 the same year, Peter Foretic gassed himself the day after giving evidence about pedophilia. On September 23, Detective Senior Constable Wayne Johnson shot himself and his estranged wife after being adversely named in the royal commission. On November 4, David Yeldham, a retired judge about to face the royal commission on questions of sexual impropriety, killed himself. A month later Danny Caines, a plumber and police confidant, committed suicide at Forster, on the North Coast.

Altogether, 12 people enmeshed in the Wood royal commission took their own lives. Scores of others were so profoundly affected by proceedings that their supporters and families believe it shortened their lives. A former detective, Greg Jensen, suffered a recurrence of the stomach cancer that ultimately ended his life, while another former detective, Ray McDougall, who faced the threat that commission investigators might expose his extramarital affair if he did not co-operate, succumbed to motor neurone disease.

There is no doubt that the Royal Commission into the NSW Police Service, headed by the Supreme Court judge James Wood, purged the force of a rollcall of rotters. A total of 284 police officers were adversely named, 46 briefs of evidence were sent to the Director of Public Prosecutions and by 2001 nine officers had pleaded guilty to corruption offences and three not guilty. Seven police officers received jail sentences, including the former Gosford drug squad chief Wayne Eade and a former chief of detectives, Graham “Chook” Fowler.

Several high-profile police ended their careers in disgrace, including Ray Donaldson, an assistant commissioner, whose contract was not renewed, and Bob Lysaught, the commissioner’s chief of staff, whose contract was torn up. Charges against 14 officers were dismissed because of irregularities in search warrants and their execution.

That left the question of what to do with police who were on the nose but who could not be brought to account by normal means. The solution was the creation of section 181B of the Police Service Act, under which the police commissioner could dismiss an officer on the basis of what had come out of the royal commission. Section 181D allowed the police commissioner to serve an officer with a notice indicating that he “does not have confidence in the police officer’s suitability to continue as a police officer”. The officer could show cause as to why he should be retained, and if dismissed could appeal to the Industrial Relations Tribunal.

Another former policeman, Dr Michael Kennedy, says the commission was a political response to the police commissioner, Tony Lauer, bringing about the downfall of the then police minister, Ted Pickering.

The attorney-general, ministry and judiciary took little responsibility for the state of the force, Kennedy says, while the responsibility of the police rank-and-file grew to “the size of a Pacific driftnet”. “I don’t think the royal commission contributed anything to the reform process except to provide a template for double standards,” he says.

CRUSADER WHO MADE THE CALL

JOHN HATTON well remembers the audience on May 11, 1994, when he made his speech calling for a royal commission into the NSW Police Service. MPs were listening, of course, but it was a gallery above him, packed with the “top brass of the police force – the commissioner himself, the deputy commissioner, superintendents – they were an intimidating force on the Parliament”.

“They thought they could stare down the Labor Party support for my motion,” Hatton, now retired, says. “It was probably the best indicator of the way in which the police force thought they could control the agenda.”

Hatton won the day, putting paid to a claim by then police commissioner, Tony Lauer, that “systemic corruption” was “a figment of the political imagination”. Hearings started on November 24, 1994, and Justice James Wood delivered his final report on August 26, 1997.

Ten years later, Hatton believes he was vindicated. He says Wood was “the right man” to head the commission and the recruitment of interstate police was crucial, along with the decision to use phone taps and surveillance.

The 11 volumes of material Hatton gave the royal commission had been accumulated over 14 years, he says, from the time he had first spoken up. He had received information on illegal gambling, drug trafficking and police involvement with the mafia.

There had been earlier moves to address police corruption, including inquiries by the Independent Commission Against Corruption, but these had only scratched the surface. “I can remember on one occasion I reported a death threat which had to do with the McKay murder in Griffith and 48 hours later the bloke who had given the information was threatened by a shotgun at his door in Queensland,” Hatton says.

The royal commission came into being because Hatton and other independent MPs held the balance of power in Parliament. The Labor Party may have had high public motives, but also saw a chance to attack the Fahey government. Labor stipulated that an inquiry into police protection of pedophiles, previously in the hands of the ICAC, become part of the royal commission.

The process of gathering information was helped greatly by Trevor Haken, a detective who became an informer and covert investigator as part of a deal to avoid being prosecuted himself.

Hatton says Haken‘s entry was “out of the blue”. Though useful, in the long term it had had a detrimental effect on the fight against corruption. Living in fear and watching his back, Haken had provided “the greatest disincentive for someone coming forward to finger corruption in the system”.

Malcolm Brown

One Comment