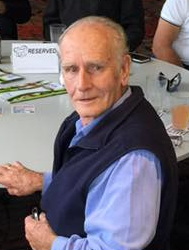

George William SLADE

George Walter SLADE

NSW Police Training Centre, Redfern – Class # 068

New South Wales Police Force

Regd. # 8591

Rank: Commenced Training at Redfern Police Academy on Monday 4 February 1957 ( aged 25 years, 4 months, 15 days )( spent 1 month, 28 days at Academy )

Probationary Constable – appointed 1 April 1957 ( aged 25 years, 6 months, 12 days )

Constable – appointed 1 April 1968

Constable 1st Class – appointed ? ? ?

Detective – appointed ? ? ? ( YES )

Senior Constable – appointed 1 April 1968

Sergeant 3rd Class – appointed 6 May 1973

Sergeant 2nd Class – appointed ? ? ?

Sergeant 1st Class – appointed ? ? ?

Final Rank: Detective Sergeant

George does NOT appear in the 1979 Stud Book despite appearing to be a Detective in the 1980s with BCI

Stations: ? , Liverpool, Fairfield ( 34 Division ) Detectives – late 1970’s – 1980’s, ?

Bureau of Crime Intelligence ( BCI ) – 1980’s – 1982 – retirement

Service: From 4 February 1957 to ? ? 1982 = 24+ years Service

Awards: No Find on Australian Honours system

Born: Sunday 20 September 1931

Died: Wednesday 7 August 1996

Cause: Illness – Cancer

Age: 64 years, 10 months, 18 days old

Funeral date: Monday 12 August 1996

Funeral location: All Saints Church, Victoria Rd, Parramatta

Grave location: ?

There was also a K. SLADE # 7236 – Born August 1927 – who was a Sgt 3/c on 1 Jan 1968 at the same time George was a Senior Constable.

There was also R.G. SLADE # 16273 – Born 1954 who was a Constable on 8 April 1975.

It is not known if they were related.

Colin Winchester And The Calabrian Connection

Sydney Morning Herald

Friday August 18, 1989

Evan Whitton

THE Winchester inquest will be conducted by the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) Chief Magistrate, Ronald Cahill, assisted by the Deputy Federal Director of Public Prosecutions, John Dee, QC, in the AMP Building, Hobart Place, Canberra.

Winchester, 55, third in seniority in the Federal Police, and said to be nicknamed The Dog because of his dogged tracking of criminals, drove in his unmarked police car to his home in Lawley Street, Deakin, after work on Tuesday, January 10, 1989.

He had a drink with his wife, Gwen, and then drove to Queanbeyan to discuss a proposed hunting trip with his brother Ken. He returned about 9.10pm and parked his car in the driveway of their next-door neighbour’s house. He was wearing a track suit, no socks, and Adidas running shoes.

Winchester turned off the lights and engine, opened the door, and put one foot on the ground. His head framed by the interior light, he was a perfect target. A person stepped forward in the dark to within two or three metres of the car and shot Winchester twice, on either side of the right ear, with a silenced .22 self-loading 10/22 Ruger rifle. Winchester died instantly. He slumped back in the seat, still holding the car keys and with his right foot still on the ground.

Unlike NSW, where an inquest is held into every homicide, an inquest is held in the ACT only if police are not able to lay charges. However, if sufficient evidence emerges, Mr Cahill has the power to turn the inquest into a committal hearing. He can also imprison witnesses who refuse to answer questions.

The first leg of the inquest is scheduled to run for five weeks, until September 22. There will then be a break of two weeks, and the inquest will then run until it is finished. This is currently expected to take between a week and three weeks.

The inquest will examine material relating to various possible scenarios. Dee has stated that the inquest will proceed in three parts: formal matters; evidence on investigations in which Winchester had been involved; and information on people who might have held a grudge against him. Within that framework, the material will be subdivided into separate blocks.

THERE is political and media speculation that the Winchester killing, like the 1977 assassination of Donald Bruce Mackay, may turn on marijuana and the profits to be made there from by elements of organised crime, including what may be termed the Calabrian Mob and corrupt police.

From the following data, and the comparative brevity of the inquest, it may be thought that what is required is not so much an inquest as a full-scale commission of inquiry, with terms of reference and powers as wide as those lately enjoyed by Fitzgerald, QC, in Queensland, to examine the operations of the Calabrians and the possible nexus between them and law enforcement authorities and politicians.

Calabria is a province in the toe of Italy. A Calabrian village, Plati (pop. 3,000), is the headquarters of a secret society, L’Onorata Societa (The Honoured Society) or N’Dranghita. This is not to be confused with other Italian secret societies, the Mafia proper from Sicily, or the Camorra from Naples. Migrants from Calabria began arriving in Australia in 1928. Many went to Griffith, 600 kilometres south-west of Sydney. More Calabrians arrived after the war.

Marijuana, one of many names given to the treated form of the cannabis or Indian hemp plant, became, as a legacy of the Vietnam War, a recreational drug in Australia in the mid-1960s. Cannabis will grow anywhere there is heat and water. Seedlings are planted around August and the crop taken off in January or February.

Justice Woodward reported in 1979 that people born in Plati were involved between 1974 and 1978 in at least 20 cannabis plantations in all mainland States except Victoria. The Australian Bureau of Criminal Intelligence, established in 1981, adopted as its first project, codenamed Alpha, the collection of data on the activities of Italian-oriented cannabis operations.

One cannabis plant was estimated in 1986 to produce $1,100 worth of manufactured marijuana at street level. It has been suggested that Australian marijuana is now being exported, and profits used to finance importation of heroin, cocaine and crack.

It is convenient to examine the Griffith/Calabrian matter in three overlapping sections: Robert Trimbole 1970-87; Joe Verduci 1980-89; Luigi Pochi 1975-89.

THE CHARMED LIFE OF ROBERT TRIMBOLE

IT is said that the Calabrians prefer to co-operate with police rather than shoot them. Gianfranco Tizzoni was an informer for Melbourne police, Customs and narcotics agents. He and another Calabrian informant, Giuseppi (Joe)Verduci, afford useful examples of the ambiguity inherent in the relationship

The informer is assumed to be working for the authorities, but he may be able to arrange matters so that the police are actually working to protect his interests, and to disrupt the activities of his criminal competitors.

Robert Trimbole was a leading member of a Griffith element of N’Dranghita called The Family (La Famiglia). Tizzoni later said Trimbole asked him in 1971 to arrange distribution in Melbourne of unlimited supplies of cannabis from Griffith. Justice Woodward later found that Griffith cannabis growers were protected by local detectives John Ellis, Brian Borthwick and John Robbins. All three were eventually imprisoned for perverting the course of justice.

Bob Bottom discloses in his book Shadow of Shame, sub-titled How the Mafia Got away with the Murder of Donald Mackay, that Mackay, a Griffith businessman and Liberal politician, sent John Maddison, then Minister for Police in the Liberal NSW Government, a confidential dossier on Calabrian involvement in drugs in July 1975. Mackay invented the term “grass castles” to describe ornate homes built in Griffith for former peasant farmers, and said that Trimbole, recently a bankrupt, was thought to provide the Sydney outlet for cannabis.

Maddison took no action, but Sydney police, acting on a tipoff from Mackay, raided an $80-million plantation at Coleambally in November 1985. A number of people were charged and convicted, including Luigi Pochi, of Canberra, who was sentenced to two years in prison in March 1977.

Tizzoni later stated that Trimbole told him to get someone from Melbourne to eliminate Mackay. He said he arranged through a gunsmith, George Joseph, for James Frederick Bazley to execute Mackay. He said Bazley asked for and got no more than $10,000, and that Joseph asked for 10 per cent of the fee, $1,000, for the introduction. Mackay was assassinated in Griffith on July 15, 1977. Bazley, who was eventually convicted of the crime, claims that the killer was actually former NSW detective Fred Krahe.

Bottom records that false rumours to the effect that Mackay had decamped with a woman were floated by two press secretaries in the Wran Government, by a senior Cabinet minister, by a senior police officer, and by Krahe in Griffith. NSW police, led by Sergeant Joe Parrington, were baffled.

Justice Philip Woodward began a royal commission on drug trafficking in August 1977. Observing the Griffith “grass castles” from outside, Woodward, who had fewer powers of entry than the fruit fly inspector, sought an extension of his powers to give him ingress. This was refused by Premier Neville Wran on civil liberties grounds.

Tizzoni later said that Trimbole, who bought into the Mr Asia heroin syndicate in 1979, arranged through Tizzoni, Joseph and Bazley to dispose of drug couriers Douglas and Isabel Wilson, who had informed on syndicate head Terence Clark to Brisbane police and narcotics agents in June 1978. The Wilsons were murdered near Melbourne in April 1979.

Woodward reported to the NSW Government in November 1979 that he was satisfied that Calabrians in Griffith directed a cannabis-growing and distribution network, and that “this organisation was responsible for the disappearance and murder of Donald Mackay”. He recommended that a task force be set up to monitor the activities of Trimbole and his associates. No such task force was set up. Trimbole told The Sydney Morning Herald in November 1979: “That commission can’t touch me or charge me in any way.”

Under subpoena, Trimbole was to appear at the Wilsons’ inquest on August 12, 1980. An inquiry by John Nagle, QC, later found that shortly before that date former Labor parliamentarian Albert Jaime Grassby unsuccessfully sought to have tabled under privilege in the NSW and South Australian parliaments a document falsely suggesting that Mackay’s widow, her son, and her solicitor, had conspired to murder Mackay. Grassby later apologised and agreed to pay$5,000 to cover Mrs Mackay’s court costs to end a defamation action she initiated against Grassby.

Trimbole did not give evidence at the Wilsons’ inquest on the ground that his answers might tend to incriminate him. The coroner recommended an inquiry be held into the Mr Asia syndicate. Trimbole fled the country in May 1981 to avoid giving evidence at Justice Stewart’s inquiry, and apparently worked at organising drug and arms running from bases in France, Italy, Switzerland and Ireland.

The Australian Government had been negotiating in desultory fashion with the Irish Government for an extradition treaty since 1977. Bottom notes that on April 1, 1982, the day Trimbole’s stepdaughter took up residence at an exclusive girls’ school in Ireland, some unknown person removed the file on the treaty from an active tray; marked it “no further action required”; and buried it in the Federal Attorney-General’s storage vault.

Justice Stewart recommended to the Federal and NSW governments in August 1982 that Trimbole be found and extradited, but Australia still had no extradition treaty with Ireland when Irish police arrested Trimbole in Dublin in October 1984.

The arrest was tainted, and an Irish court ruled in February 1985 that Trimbole should be released. He retired to Spain and lived there, untroubled by Spanish or Australian authorities, for a further two years before dying, no doubt to the relief of many in Australia, of a heart attack on May 13, 1987. A Catholic priest with a sense of humour, Father John Massore, later conducted a funeral service for Trimbole in Smithfield, Sydney. He took as one of his themes: all human life is as grass.

JOE VERDUCI AND OPERATION SEVILLE

COLIN Winchester, a former miner then 29, joined the ACT police force in 1962. Some of the ACT police were said to act like country cousins of Sydney police, and rather looked up to some of the more flashy, if dubious, detectives therein. It has been asserted that Winchester was corrupt, at least at any earlier period when he is said to have handled bribes relating to a Canberra illegal casino. However, an audit of his financial affairs after his murder revealed nothing untoward.

The ACT Police and Commonwealth Police were merged in 1979 to form the Australian Federal Police (AFP). Channel 10 reporter Christopher Masters says that factional infighting deriving from the original divisions remain, and have impeded the Winchester investigation.

Giuseppi (Joe) Verduci offered in late 1980 to supply AFP Detective Sergeant Brian Lockwood with information on members of the Canberra Italian community allegedly involved in organised crime. Lockwood says that in August 1981 Verduci said he had been approached by Luigi Pochi and another man about growing marijuana on his property at Bungendore, in NSW, just outside the ACT

Bottom notes in Shadow of Shame that Lockwood advised his superior, Winchester, and that Winchester and Bob Blissett, then head of the NSW Bureau of Criminal Intelligence (BCI), agreed to allow the plantation to run as a joint “controlled” operation code-named Operation Seville. The approval of NSW Commissioner of Police, Cecil Abbott, was subsequently obtained, and the operation was placed under the direct control of Winchester and Detective Sergeant * George Slade of the NSW BCI.

The theory was that surveillance would enable police to establish distribution routes and to identify distributors and financiers, and thus, perhaps, get evidence against the Calabrians. Bungendore I was planted in August 1981. Independent NSW MLA John Hatton later asserted that, including Bungendore, there had been 14 drug crops in southern NSW, at Braidwood, Dalton, Michelago and in the Brindabella ranges, of which at least 13 had been grown with the supervision or knowledge of NSW police.

Bungendore I was harvested in February 1982. Some 50 kilograms were sent to Sydney on March 18. The shipment was kept under surveillance and photographed ; no arrests were made. Lockwood said he handed on to Winchester $23,500 given him by Verduci as a result of the operation in March 1982. Winchester paid the money into Consolidated Revenue in September 1982.

At a later court hearing, Verduci declined to answer, on the ground that it might incriminate him, a suggestion that Verduci had paid Winchester large cash amounts that had not gone into Consolidated Revenue.

Robert Trimbole’s old friend, Gianfranco Tizzoni, and two others took the rest of the crop to Victoria. Alerted by NSW police, Victorian police arrested them on March 31 and charged them with possession and supply of marijuana and unlawful possession of firearms.

Tizzoni began to negotiate with Victorian detectives and eventually supplied information that led to the convictions of himself, George Joseph and James Bazley in connection with the murders of Donald Mackay and the Wilsons. So to that extent Operation Seville was a success.

Bungendore II was seeded as part of Operation Seville, of which Winchester was no longer part, in August 1982. Armed assaults were made on the plantation in January 1983 by criminals, possibly at the behest of corrupt NSW police. After these debacles, police destroyed the remainder of the crop in February 1983, and closed down Operation Seville.

AFP Detective Sergeant John Best took over Verduci as an informant from Lockwood in mid-1984. In August, Verduci, apparently without AFP or NSW police authority, became involved in seeding 44,000 hemp plants, worth $50 million on the street, on a plantation at Guyra on the New England tablelands.

Detective Sergeant Bob Small of Armidale police arrested Verduci and five labourers on the Guyra plantation on November 15, 1984. Verduci claimed he had immunity from the AFP. Small checked with Best, who said he had no immunity at Guyra. Best recommended that Verduci be dropped as an AFP informant.

Four of the Guyra labourers pleaded guilty and were each sentenced to 5 1/2 years, with a minimum of three years, on July 1, 1986. A fifth, Carmelo Micalizzi, pleaded not guilty and was tried separately.

At one stage, NSW Crown Law authorities were of a mind to charge Verduci and everyone else, Calabrians and police alike, involved in the Bungendore operation, but this was seen as too much of a problem, and the whole thing was handed over to the National Crime Authority (NCA) for evaluation in 1987.

In July 1987, Winchester was formally warned and interrogated by NCA Chief Inspector Robert McDonald about his role in the Bungendore affair. The NCA concluded that Winchester had done nothing illegal.

The NCA used the trial of Micalizzi in November 1987 as a sort of dry run to see how Verduci might perform as an indemnified Crown witness against Calabrians allegedly involved in the Bungendore operation. Micalizzi was found guilty and got 5 1/2 years with a minimum of three. Thus encouraged, the NCA charged 11 people, including Luigi Pochi, in April 1988 in connection with the Bungendore matters.

The Bungendore committal hearing was to start in Queanbeyan on February 6, 1989. Winchester might have been a witness, but not as important a witness as Verduci, who did not appear to feel that he was at any sort of risk ; he had declined to continue to accept police protection.

When Winchester was executed on January 10,Lockwood, now a Canberra service station proprietor,was given police protection. AFP Commander Lloyd Worthy, a former member of the ACT Police, was in charge of the investigation.

More than 25 police, led by Chief Superintendent Richard Ninness, raided the flat of a former Treasury official, said to have held a grudge against Winchester, on January 18, but Worthy said there was no suggestion the man would be charged in connection with the murder.

Verduci refused to give evidence in the Bungendore case, and most of the charges were withdrawn on March 1 ; NSW Attorney-General John Dowd dropped the remaining charges against the Calabrians in May.

THE CHARMED LIFE OF LUIGI POCHI

AS noted, Luigi Pochi was sentenced to two years in prison in March 1977 in connection with a cannabis plantation at Coleambally. Pochi, who had come to Australia in 1959, was eligible for deportation because he had not, through an administrative bungle, become an Australian citizen.

Michael Mackellar, Federal Immigration Minister, ordered Pochi’s deportation in 1978 on the ground of his conviction and alleged involvement in “commerce in marijuana”. Pochi appealed.

Mr Justice Gerard Brennan, president of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT), recommended in 1979 that Pochi not be deported. He said there were ample grounds for suspecting that Pochi was involved in marijuana, but the evidence did not prove it ; such conduct “must be proved,not merely suspected”

Justice Woodward found in November 1979 that he was satisfied that Pochi was a Canberra principal of the Griffith cannabis organisation ; that the growing of cannabis was principally supervised from Griffith by Pochi’s brother-in-law and business partner, Antonio Sergi ; and that distribution and marketing was supervised principally by Pochi’s other business partner, Robert Trimbole. Sergi has never been charged with any crime.

The Federal Court upheld Justice Brennan’s recommendation against deporting Pochi in July 1980. The Government appealed to the High Court. The High Court refused leave to appeal in August 1981, a time when Pochi was later alleged to have been involved in Joe Verduci’s Bungendore plantation.

Pochi had received support from elements of the Labor Party. It has been reported that in 1981 Verduci was said to have gone to the home of a Labor Party figure to warn him that the party should not be seen to be supporting Pochi and that he even produced marijuana from the Bungendore crop “to show the ALP man that Pochi was involved in drugs”.

Ian MacPhee, then Liberal Immigration Minister, who might have had access to current intelligence not available to others, overruled the AAT recommendations on February 23, 1982, and had a deportation order served on Pochi giving him 72 hours to leave the country.

Pochi issued a statement asserting: “I have always denied and still deny that I had any association with any illegal criminal organisation.” He obtained a temporary High Court injunction to stay his departure.

The High Court unanimously upheld the validity of the Pochi order on October 22, 1982, but Justice Lionel Murphy added it would be a misuse of power to deport Pochi in circumstances that might break up his family.

Three days later, the then Immigration Minister John Hodges, who had replaced MacPhee in May, revoked the order “on strong humanitarian and compassionate grounds”. On October 27, 1982, the Taxation Commissioner’s annual report showed that Pochi, 43, had been fined $16,000 for underestimating his income by $57,671 in the period between 1973-74 and 1975-76.

Pochi was among 11 charged in April 1988 in connection with the Bungendore plantation. He and three associates were members of the Belconnen branch of the Australian Labor Party at the time of the Winchester murder on January 10, 1989. It was later reported that police had sought the records of a branch meeting held on that night.

As noted, the case against Pochi and others collapsed in March 1989 when Verduci refused to give evidence.

His middle name was Walter, not William

Hi Richard,

Thank you for that correction. George’s Memorial has been updated and additional information also added.

Would you send me the details to answer the outstanding red question marks and also, if you have any, some photos of George.

I used to work with George when he was at Fairfield back about 1978.

regards

Cal