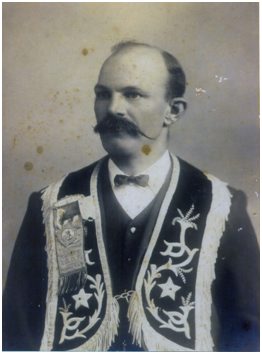

Edwin Stuart HICKEY

Edwin Stuart HICKEY

New South Wales Police Force

Sergeant 2nd Class

Officer In Charge – Pymble Police Station

Shot – Murdered

Pitt Water Rd, St Ives

Joined NSW Police Force in 1881 or 1891

Died 1 May, 1913

52 old

Funeral date: ?

Photo supplied by Val Fearby

The sergeant was shot to death at the Sydney suburb of St Ives while trying to arrest an offender named Brown on warrants. On the day of his death the sergeant and Constable Barclay attended the offender’s home and while inside the dwelling, told Brown he was under arrest. He began to resist violently before drawing a revolver and shooting Sergeant Hickey three times. The offender made good his escape however was arrested a short time later by Constable Barclay. The sergeant’s wounds unfortunately proved to be severe and he died a short time later at the Royal North Shore Hospital. The offender’s son was also shot in the arm during the incident.

The sergeant was born in 1861 and joined the New South Wales Police Force on 29 October, 1881. At the time of his death he was stationed at Pymble.

[blockquote]Hickey has been in charge of the Pymble Police Station for over twenty five years

http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/102941208?searchTerm=%22police%20sergeant%20kill%22&searchLimits=[/blockquote]

St John’s ( Anglican ) Cemetery, 754 Pacific Hwy, Gordon, NSW.

Ref: CC17

ACTION STRUCK OUT. INJUNCTION TO RESTRAIN GRANTED. SYDNEY.

Friday. ( 19 April 1912 )

There was brought before Justice Simpson in the Common Law Chambers to-day a case in which Thomas Edward Brown, of St. Ives, near Gordon, made claim for £20,000 against a big list of defendants, including the Attorney-General (Mr. Wade, M.L.A.), several Supreme Court judges, most of the stipendiary magistrates, the Inspector-Generol (sic) of Police; and the Kuringai Shire Council. Plaintiff complained that various legal proceedings had been maliciously used against him, and, that he had been deprived of legal rights. Counsel representing defendants asked that plaintiff’s declaration be struck out, and that plaintiff be restrained from further proceedings of a like character against them. It was pointed out that Justice Ferguson had previously struck out an action by plaintiff against some of the present defendants.

Justice Simpson granted the application and the injunction as asked for on behalf of the defendants.

Examiner ( Launceston, Tasmania ) Saturday 20 April 1912 Page 8 of 12

A SHOOTING TRAGEDY.

SERGEANT OF POLICE KILLED,

AN ARREST MADE.

SYDNEY, May 1. ( Thursday )

A police official was the victim of a shooting tragedy which took place this morning at St. Ives, an orchadists settlement on the north coast railway line.

It appears, that Sergeant Hickey, who for upwards of 20 years has been in charge of the police-station at Pymble, accompanied by Constable Barclay, proceeded to the residence of Thomas Edwin Brown an orchardist residing on Pitt water-road, St. Ives. The mission of the police was to arrest Brown on two commitment warrants. One warrant, it is stated, was in connection with the non-payment of costs in an appeal case, and the other is related to the non-payment of a small fine and costs in connection with a traffic summons case.

The police found the man they were looking for in his orchard, where he was working with his sons. They indicated to him the nature of their business, and then invited Sergeant Hickey and his companion up to the house, and, turning to one of his sons, said, “You had better come, too.” They all went to Brown’s residence on the opposite side of the orchard.

Brown and his son entered the door, followed by Sergeant Hickey, with Constable Barclay in the rear. Barclay states that no sooner had they got inside than Brown, sen., without warning, produced a revolver, and fired point blank at Sergeant Hickey. He fired altogether four shots. Three of them took effect in the Sergent altogether and in the scuffle which immediately followed a fourth shot lodged in the arm of Brown’s son, who had intervened to prevent further shooting.

Sergeant Hickey fell to the floor, and never spoke.

Constable Barclay immediately ran for assistance, and he met two men named Rogers and McIntosh, and told them what had happened. They ran down to Brown’s house, and then they found Sergeant Hickey lying on the floor in an unconscious condition. They conveyed him to the local police station, and he was quickly conveyed to the Royal North Shore Hospital, but be died a few minutes after admission.

Later young Brown who also had been shot, was brought to the institution, and admitted with a bullet wound in his arm.

After informing the two men, Rogers, and McIntosh, of the shooting, Constable Barclay discovered that Brown, sen., had left the house, and was down the Gordon road. He went in pursuit, and, finding Brown, covered him with his revolver, and ordered him to surrender and to throw up his arms. Brown surrendered quietly, and Constable Barclay, finding, by searching him, that Brown was not then in the possession of firearms, arrested and escorted him to North Sydney, where he was locked up on a charge of shooting.

The late Sergeant Hickey was a greatly esteemed officer. He was on the eve of retiring from the service, which he joined in 1891.

The Mercury ( Hobart, Tasmania ) Friday 2 May 1913 Page 5 of 8

Police Sergeant Shot.

An Orchard Tragedy

SYDNEY, May 1.

A shocking tragedy was enacted at St. Ives this morning. In attempting to serve two committment, warrants an an orchardist residing at Pymble, Sergeant Edward Hickey was fired on, and so badly wounded that he died shortly after admission to the hospital.

The man who to alleged to have done the shooting has a large-sized orchard off Pittwater Road, St. Ives, which runs from Pymble right through to Pittwater. He has been associated a good deal with law matters, and although regarded as an eccentric, has never been looked upon as being dangerous or likely to be subject to outbursts of violence. He is alleged to have produced a revolver and fired four shots. Three of the bullets lodged in Hickey’s body, and he fell to the ground mortally wounded.

Constable Barclay went in search of the orchardist, and having secured him, handcuffed him, and took him to the police station. Later on he was brought down to the North Sydney Police Station, and charged with murder. He gave his name as Thomas Edwin Brown.

Cairns Post ( Qld ) Friday 2 May 1913 Page 5 of 8

The Clarence and Richmond Examiner of 17 May, 1913 printed the following article relating to the inquest into the sergeant’s death.

SYDNEY, Thursday — An inquest was commenced concerning the shooting of Sergeant Hickey at St Ives. Thomas Edwin Brown, who was charged with murder, was present in custody. Constable Barclay deposed that Sergeant Hickey informed Brown that he had two commitment warrants and that unless Brown paid the money he would place him under arrest and convey him to Darlinghurst Gaol. Brown remarked that warrants were illegal and as witness reached the dining-room door of Brown’s house the latter said, “Go back, you can’t come in here; it’s illegal. Sergeant Hickey closed with Brown, who immediately fired three shots at him. Witness drew a revolver and stated that unless Brown put his hands up he would put a hole through him and Brown put them up, at the same time remarking, “I’m sorry, I am prepared to die.” When asked why he shot Sergeant Hickey he replied that he was driven to it. The Coroner found that the deceased died from a revolver wound feloniously inflicted on him by Brown who was committed for trial on a charge of murdering him.

THE ST. IVES TRAGEDY.

BROWN APPEALS FOR BAIL.

THE APPLICATION REFUSED.

Sydney, Wednesday Afternoon. ( 14 January 1914 )

Thomas Edward Brown, charged with the murder last year at St. Ives of Sergeant Hickey, made application this morning, to Mr. Justice Gordon in the Supreme Court for bail. Brown has already been tried once, but a new trial was granted by the High Court, and has now been in gaol nine months.

Mr. d’Apice appeared for the Crown to oppose the application, and Brown appeared in person. Brown said he would like the application to stand over until later in the day, as on coming to the court he had met some of his children and had been considerably upset.

His Honor refused to grant any adjournment.

Brown then submitted that bail should be granted, so that he might have the fullest opportunity of preparing, his defence. He had been placed in the section of the gaol allotted to murderers.

His Honor said, the Crown case was thoroughly known; therefore, it was much easier for the accused to prepare his reply in the second case. Even if the Crown consented, his Honor said he did not know that he should consent to the prisoner’s release. He therefore, refused the application.

Mr d’Apice said the gaol authorities would give the prisoner every opportunity for the preparation of his defence.

The prisoner, was then recommitted to gaol and removed in custody.

Barrier Miner ( Broken Hill, NSW ) Thursday 15 January 1914 page 6 of 8

NEW SOUTH WALES

RECENT CASE REVIVED.

SYDNEY. April 27.

Thomas Edwin Brown, of St Ives, orchardist, who was recently acquitted on a charge of having murdered by shooting Police Sergeant Hickey, has been adjudged insane by a special court of inquiry. He has consequently been ordered to be detained in an Asylum. Notice of appeal has been given on Brown’s behalf.

The Brisbane Courier ( Qld ) Tuesday 28 April 1914 Page 7 of 10

QUESTION OF SANITY

THE BROWN CASE.

DEEMED TO BE INSANE.

A special Court to consider the question of the sanity of Thomas Edwin Brown, of St. Ives, who was acquitted at the Central Criminal Court last month on a charge of having murdered Sergeant Hickey, but who was detained on his release on a charge of insanity, was held at the Reception House at Darlinghurst on several days this month. Mr. J. McKensey, deputy stipendiary magistrate, presided, and at the final sitting on Saturday last, Brown was deemed to be insane.

The exhibits in the case consisted of a number of voluminous documents, in the majority of which Brown mentioned grievances which he considered that he had. One of these was a petition addressed to Lord Chelmsford, asking for the appointment of a Royal Commission to inquire into his case. It consisted of 10 pages of typewritten matter, and was forwarded on March 18, 1912. In it Brown said that the legal process of the State was denied to him, and that he intended to protect himself, family, and property from injury by “these blackmailers of the Crown.” He also went on to say that he would not be responsible for any consequences of his acts, “but will claim to be exonerated from blame from this date during this state of siege, irrespective of evidence taken, as they now concoct evidence for an excuse to punish with, for any act which may be done in a mistaken apprehension of danger or otherwise.”

Mr. Garland, K.C., instructed by Mr. Robinson, appeared on behalf of the Crown; and Mr. Ralston, K.C., instructed by Mr. McElhone, on behalf of Brown.

Dr. Palmer, First Government Medical Officer at Sydney, said that he had known Brown since May 2 last year, and had frequent opportunities of observing him and conversing with him. “I am of the opinion that he is insane,” said the doctor. “For the purpose of making a certificate to that effect I examined him separately. His form of insanity is called paranoia, or systematised delusions. In my opinion the only proper care and control of a person so suffering is to be had in an institution. The chief characteristic of that variety of insanity is that the person suffering is potentially homicidal. For the sake of others, as well as himself, he should be detained in an institution.”

In answer to Mr. Ralston, witness said that Brown had been tried three times for murder, but the Crown or anyone else did not raise the question of his sanity. He was of the opinion of his examination of Brown was right that he would not get better. His insanity might become modified, and perhaps take on a different form. He was sound physically, and had never complained of sickness. The delusion he suffered from was that a combination of public officials was persecuting him.

Dr. Andrew Davidson said that he had had a large experience in mental cases, and for three years was medical superintendent at Callan Park Asylum. He had seen Brown on a number of occasions, and was of the opinion that he was suffering from chronic systematised insanity. His form of insanity was one that generally became worse. In certain cases it was dangerous. “The fact that Brown was arrested for being insane would not necessarily worry him,” said the doctor. “A sane individual would, to a certain extent, be worried. He does not wear such a worried expression now as he did.”

Dr. Eric Sinclair, Inspector-General of Insane for 16 years, said that he had seen Brown, and also some of the letters which he had written, and was of the opinion that he was insane. “The probabilities that his delusions will continue are very strong, indeed,” said witness. “As far as we know medically, they will continue, but one hesitates to say for certaln what will happen in the future. If it were proved that his delusions have disappeared now, it is obvious that he is not insane at the present time. Assuming on April 2, that Brown had informed Dr. Palmer that he was going to America, as he could not get justice here, I would be inclined to consider that was an indication that the delusions had not disappeared.”

Dr. Chisholm Ross said that after seeing Brown and some of the documents written by him, he should say that the man thought that he was being persecuted. “I say that, if he was not insane, he was preparing for persecutionary paranoia,” continued the doctor. “Cases of this disease are persistent, and as a rule persons suffering from it recover very rarely, if at all. If not under restraint they are a danger to themselves and others.”

In reply to Mr. Ralston, Dr. Ross said that he had been dealing with mental cases for 30 years. He gave a certificate that Brown was a fit subject for examination. He did not give a certificate of his insanity. He had not seen any indication in Brown of paranoia, or any other form of insanity. He was unable to give a certificate that Brown was insane.

Drs. Alfred Walter Campbell and George Edward Ronnie declared that Brown was insane.

David Ross Jamieson, Acting Under-Secretary in the Department of Justice, said that Brown called on him at his office, and said that he wished to make a complaint about the administration of justice. He handed witness a document, and, when it was returned to him he (Brown) said “I can’t get justice from anybody; the Judges won’t hear me; the Stipendiary Magistrates won’t hear me; and the Chamber Magistrates will not issue process for me. I can’t get assistance or protection from the police, and am in fear. I have a weapon and will have to use It.” He was told to complain to the Inspector-General of Police if the police refused to assist him, and he left the room.

Evidence for the Crown having closed, Mr. Ralston submitted that Brown was illegally before the Court, as he had been illegally arrested, and that there was no evidence adduced to prove that Brown was found under circumstances indicating that he was likely to commit some offence against the Law. He considered that the inquiry was a nullity, and that Brown should be discharged.

Mr. McKensey said that it was not for him to decide whether Brown was legally or illegally arrested, and overruled the objection.

On behalf of Brown, Dr. Richard Arthur said that he had a conversation with Brown which lasted an hour and a half, and he saw no signs of mental aberration after he had used a number of methods to prove his mental unsoundness. He had heard some of the documents read, and he still adhered to his opinion. The statements made were severe, but they were not in any way exceptional.

Dr. Sydney Jamieson said that when he saw Brown on March 30 he mentioned the question of his having the idea that he was being persecuted, and his attempts to stop those supposed persecutions, but Brown laughed and treated it as a matter of levity. He said: “It is quite true, I signed those documents.” He was then asked by witness if he still thought that he was being persecuted, and he replied: “I wouldn’t say that, but I think that at the time I was very much upset, and my views on what I then wrote are different now.” “I could find no evidence of insanity,” said the doctor.

To Mr. Garland, witness said: “The impression he left with me was that at one time he had seriously entertained these views but that his subsequent experience had modified them; that accumulated experience had altered his views. If a man starts an action against 62 persons as Brown did it is evidence of wild notion. Whether it is paranoia or not depends on whether it is founded on delusion or fact. If his charges against all these officials and sects are baseless then he is a paranoic. I found no evidence of it in my examination. If I knew that the charges he made against the late Chief Justice (Sir Frederick Darley) and others were baseless I would admit that he is a paranoic.”

Dr. J. B. Nash said that he examined Brown, and could find nothing mentally wrong with him, and the documents read did not alter his opinion in the slightest. He had not examined any paranoic that he knew of.

Dr. A. Murray Oram said that after an examination of Brown he could not say that he was insane. It was quite possible that Brown had paranoia, “I say he was not sane in March, 1913, when he drew the document up,” concluded the doctor.

Thomas Henley, M.L.A., said that he had known Brown for 20 years, and had never detected any evidences of insanity.

Peter Christian Bjornstad, Acting Superintendent at the Reception House, said that Brown now appeared to be perfectly normal.

Dr. A. C. Cahill, called by the Bench, said that he was unable to certify as to Brown’s sanity or insanity because Brown declined to converse on subjects which would throw a light on his mental condition. When Brown wrote the passages charging the late Chief Justice and others with conspiracy, he was suffering from paranoia, a complaint which generally tended to get worse.

Dr. W. W. J. O’Rielly said that he had known Brown for 18 years and he had always acted as a sane man.

Dr. A. E. Perkins, on affirmation, said that he had examined Brown and considered that he was sane.

James Weymark, a wholesale fruiterer said that he had transacted business for Brown for a number of years and had never detected any signs of insanity.

Brown, sworn, said: “I would like to say a lot. The Crown drew the inference when the documents were being read, that because I asked that one of them be continued, I still persisted in my opinions; but that I deny. The statements made in those documents were written under circumstances which would make them excusable, considering that I was not well-educated and had to seek the assistance of others. I was not conversant with the meaning of all the words. I meant by ‘conspiracy’ a succession of acts which caused me to be imprisoned. Those acts were, upon appeal to the High Court, ruled to be illegal. In the language of those documents describing the various sects, I had no intention to have it believed that that was so in the generally-accepted expression of the term. But what I really meant to show was that persons of each of the orders or sects had taken part in this matter in which I had appealed. The same descriptions of persons have repeatedly assisted me in my troubles. These documents were written at a time when I was in great trouble. I was constantly being arrested. My house was being searched by day and by night, and often when I left home to go to the market I would be arrested and put in gaol. The matters I have complained of were, briefly, the result of judgments of the various Courts which have since been upset on appeal.

Through the experience I have gained since I have been in prison, I am convinced that my proceedings were altogether wrong and unwarranted.”

Brown then narrated his experiences since he was arrested on the lunacy charge, and outlined his actions in the Courts.

After other evidence was given and addresses by counsel, Mr. McKensey said: “I am satisfied that Brown is insane and is not under proper care and control, and is a proper person to be taken charge of and detained under care and treatment. I therefore direct that Brown be removed to the Hospital for Insane, at Parramatta.”

The Sydney Morning Herald Wednesday 29 April 1914 Page 11 of 26

THE PREVENTION OF MADNESS

The extraordinary divergence of medical opinion as to the sanity or insanity of Thomas Edwin Brown, who was charged with having murdered Constable(sic) Hickey, and was acquitted, but afterwards detained on grounds of insanity, cannot be passed over without comment. The evidence of no less than 13 doctors was taken in the case; and the conclusion of six of them was completely opposed to the conclusion of the other seven.’ We offer no judgment on the result the magistrate appears to have been convinced that those who said that Brown was suffering from a dangerous delusion were right, and the man goes back into detention. But what we do say is that it is high time that the medical men of this country were given such a training in the diagnosis of madness that such a conflict of evidence should in future be put almost beyond the bounds of possibility. The public, in a case of this sort, does not know which set of doctors was right; it has not the knowledge to enable it to form an opinion on that point. What it does want is the assurance that its medical men will in future obtain such training in this important department of modern medicine as will make impossible the occurrence of any of the terrible mistakes for which the absence of such training leaves only too obvious an opening.

The men who have upon them the responsibility of deciding whether a citizen is sane or insane get very little preparation for that responsibility. Indeed, there is not a single clinic in Australia where they could get a thorough training in this branch of medicine if they wished to. There are numerous schools where students in other countries are obtaining this experience, in hospitals at Berlin, Vienna, Genoa, Kiel, Glossen, at Michigan University, at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, at Baltimore, and elsewhere. But the Australian student, whose duty it will be in general practice to recognise the early mental or nervous symptoms of insanity, is practically without opportunity of qualifying himself to do so. That is simply because we are not sufficiently abreast of modern medicine to have provided institutions where the prevention of insanity is carried on, and can be studied. The cure of insanity might not be a department of medicine at all, for all the attention that is paid to it within the borders of New South Wales. Every medical man knows of the progress that has been made in the treatment of insanity elsewhere; how special hospitals and homes have been established for the treatment of it in the earlier stages, when it is often perfectly preventable; how an international committee has been formed to advance the knowledge and treatment of the curable insanity; how special branches of the outpatient departments of more than one of the London hospitals have been established to deal with it. In Australia, except in a very few cases, insanity cannot be treated until it has reached a stage at which treatment is no longer of much use. In one or two institutions founded for another purpose an attempt is being made, mainly through the energy of individual officials, to separate and cure the early stages of insanity. But there is no organised attempt to prevent insanity, and no school where the medical student can learn to recognise it. In a good many cases it really rests in the first instance with the police whether the patient may or may not receive the necessary treatment. This, it has been cynically remarked, is perhaps, after all, just as well. The average policeman does have some opportunity of seeing early cases of insanity; the average medical student does not.

The Sydney Morning Herald Thursday 30 April 1914 Page 10 of 18

1914.

(SECOND SESSION.)

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY.

NEW SOUTH WALES POLICE DEPARTMENT.

(ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR 1913.)

Printed under No. 3 Report from Printing Committee, 13 August, 1914

Four (4) constables were discharged on gratuities amounting to £607 10s., and gratuities amounting to £2,192 18s. 4d. were awarded to the widows of seven (7) members of the Force, in addition to which £94 was allowed for funeral expenses. In the case of the widow of the late Senior-sergeant Edwin S. Hickey, who was killed in the execution of his duty, a pension of £125 per annum was granted for six (six) years, at the end of which period the case will be reconsidered.