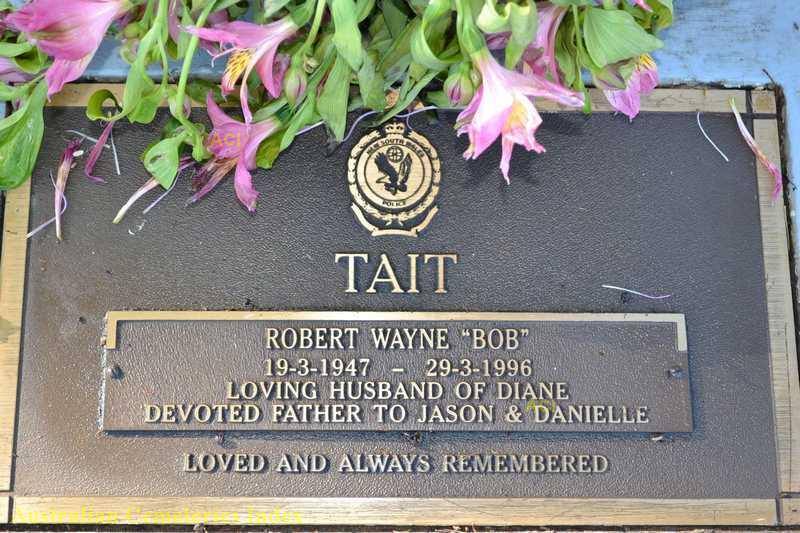

Robert Wayne TAIT

aka Bob

New South Wales Police Force

Joined via the NSW Police Cadets on 24 February 1964

Cadet # 1927

[alert_yellow]Regd. # 11786[/alert_yellow]

Rank: NSW Police Cadet – commenced 24 February 1964

Probationary Constable – appointed 19 March 1965

Senior Constable – appointed 19 March 1975

Sergeant 3rd Class – appointed 27 March 1982

Inspector – death

Stations: Narrabri – Patrol Commander

Awards: National Medal – granted 23 October 1981

1st Clasp to the National Medal – granted 28 May 1992

Service: From 24 February 1964 to 29 March 1996 = 31+ years

Born: 19 March 1947

Died: 29 March 1996

Age: 49

Cause: Illness – Suicide – Service revolver

Event location: Narrabri Police Station

Funeral: Narrabri Lawn Cemetery. Portion A2, row Q

Cremated: ?

[alert_red]Robert is NOT mentioned on the Police Wall of Remembrance[/alert_red] * BUT SHOULD BE

In 1996 Inspector Bob Tait was the officer in charge of police at Narrabri. On the morning of Friday 29 March of that year he ended his own life at the Narrabri Police Station.

The Northern Daily Leader of 30 March, 1996 reported the death.

Stunned colleagues and the Narrabri community are this morning trying to come to terms with why such a respected policeman would kill himself. Inspector Robert Tait, 49, went to work yesterday morning, where he had been serving as the patrol commander, walked into an unoccupied office, took his service revolver and ended his life.

The inspector joined the New South Wales Police Force on 24 February, 1964 as a cadet, and was sworn in on 19 March, 1966. At the time of his death he was stationed at Narrabri, where he was the patrol commander.

[divider_dotted]

http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/holding-judgement/2007/06/08/1181089328815.html?page=fullpage

It took up 451 hearing days, heard from 902 public witnesses and cost an estimated $64 million. Malcolm Brown reports on the Wood royal commission, 10 years on.

It began on June 15, 1995, when an unnamed Annandale detective jumped to his death from the seventh floor of a building, apparently through fear of the Wood royal commission. The detective’s suicide was followed by those of Ray Jenkins, a dog trainer (July 10), and Inspector Robert Tait, the acting patrol commander at Narrabri ( March 29, 1996 ). Nineteen days later a former Wollongong alderman, Brian Tobin, gassed himself.

On May 8 the same year, Peter Foretic gassed himself the day after giving evidence about pedophilia. On September 23, Detective Senior Constable Wayne Johnson shot himself and his estranged wife after being adversely named in the royal commission. On November 4, David Yeldham, a retired judge about to face the royal commission on questions of sexual impropriety, killed himself. A month later Danny Caines, a plumber and police confidant, committed suicide at Forster, on the North Coast.

Altogether, 12 people enmeshed in the Wood royal commission took their own lives. Scores of others were so profoundly affected by proceedings that their supporters and families believe it shortened their lives. A former detective, Greg Jensen, suffered a recurrence of the stomach cancer that ultimately ended his life, while another former detective, Ray McDougall, who faced the threat that commission investigators might expose his extramarital affair if he did not co-operate, succumbed to motor neurone disease.

There is no doubt that the Royal Commission into the NSW Police Service, headed by the Supreme Court judge James Wood, purged the force of a rollcall of rotters. A total of 284 police officers were adversely named, 46 briefs of evidence were sent to the Director of Public Prosecutions and by 2001 nine officers had pleaded guilty to corruption offences and three not guilty. Seven police officers received jail sentences, including the former Gosford drug squad chief Wayne Eade and a former chief of detectives, Graham “Chook” Fowler.

Several high-profile police ended their careers in disgrace, including Ray Donaldson, an assistant commissioner, whose contract was not renewed, and Bob Lysaught, the commissioner’s chief of staff, whose contract was torn up. Charges against 14 officers were dismissed because of irregularities in search warrants and their execution.

That left the question of what to do with police who were on the nose but who could not be brought to account by normal means. The solution was the creation of section 181B of the Police Service Act, under which the police commissioner could dismiss an officer on the basis of what had come out of the royal commission. Section 181D allowed the police commissioner to serve an officer with a notice indicating that he “does not have confidence in the police officer’s suitability to continue as a police officer”. The officer could show cause as to why he should be retained, and if dismissed could appeal to the Industrial Relations Tribunal.

Another former policeman, Dr Michael Kennedy, says the commission was a political response to the police commissioner, Tony Lauer, bringing about the downfall of the then police minister, Ted Pickering.

The attorney-general, ministry and judiciary took little responsibility for the state of the force, Kennedy says, while the responsibility of the police rank-and-file grew to “the size of a Pacific driftnet”. “I don’t think the royal commission contributed anything to the reform process except to provide a template for double standards,” he says.

CRUSADER WHO MADE THE CALL

JOHN HATTON well remembers the audience on May 11, 1994, when he made his speech calling for a royal commission into the NSW Police Service. MPs were listening, of course, but it was a gallery above him, packed with the “top brass of the police force – the commissioner himself, the deputy commissioner, superintendents – they were an intimidating force on the Parliament”.

“They thought they could stare down the Labor Party support for my motion,” Hatton, now retired, says. “It was probably the best indicator of the way in which the police force thought they could control the agenda.”

Hatton won the day, putting paid to a claim by then police commissioner, Tony Lauer, that “systemic corruption” was “a figment of the political imagination”. Hearings started on November 24, 1994, and Justice James Wood delivered his final report on August 26, 1997.

Ten years later, Hatton believes he was vindicated. He says Wood was “the right man” to head the commission and the recruitment of interstate police was crucial, along with the decision to use phone taps and surveillance.

The 11 volumes of material Hatton gave the royal commission had been accumulated over 14 years, he says, from the time he had first spoken up. He had received information on illegal gambling, drug trafficking and police involvement with the mafia.

There had been earlier moves to address police corruption, including inquiries by the Independent Commission Against Corruption, but these had only scratched the surface. “I can remember on one occasion I reported a death threat which had to do with the McKay murder in Griffith and 48 hours later the bloke who had given the information was threatened by a shotgun at his door in Queensland,” Hatton says.

The royal commission came into being because Hatton and other independent MPs held the balance of power in Parliament. The Labor Party may have had high public motives, but also saw a chance to attack the Fahey government. Labor stipulated that an inquiry into police protection of pedophiles, previously in the hands of the ICAC, become part of the royal commission.

The process of gathering information was helped greatly by Trevor Haken, a detective who became an informer and covert investigator as part of a deal to avoid being prosecuted himself.

Hatton says Haken‘s entry was “out of the blue”. Though useful, in the long term it had had a detrimental effect on the fight against corruption. Living in fear and watching his back, Haken had provided “the greatest disincentive for someone coming forward to finger corruption in the system”.

Malcolm Brown

[divider_dotted]

i. ROBERT TAIT

Inspector Tait was a member stationed at Narrabri in 1996. Tait received a letter from the Royal Commission, which set out:

“This is to notify you that evidence will be adduced shortly from a witness who is to be called to give evidence before the Royal Commission into the NSW Police Service to the effect that you did fail to report or investigate complaints of criminal conduct.”

There is ample evidence to support the change in TAIT ‘s demeanour and behaviour following receipt of this letter. He was seen by the Police Psychologist and his own Doctor but on the 26-3-96 he shot himself in his office with his service revolver. He left a note clearly indicating how tortured he had become as a result of being named.

http://unionsafe.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/NileInquirySubmission.doc

[divider_dotted]

Bob was my best mate, and I attended his sudden funeral as a family member.

He was a dedicated father as well as a great policmen. Buty he always had a sense of humour that I enjoyed. Miss you mate! Rod