Joseph LUKER

Joseph LUKER ( LOOKER / LUCAR )

also spelt Lucar and Looker

the first Australian police officer to be killed on duty

Late of ?

New South Wales Police Force

Regd. # ???

Rank: Constable with Sydney Foot Patrol

Stations: Sydney ( eastern side of the Settlement )

Service: From ? ? 1796 to 26 August 1803 = 7 years Service

Awards: No find on It’s An Honour

Born: ? ? c 1765 – 68

Died on: 26 August 1803 ( 15 years after the First Fleet sailed into Sydney Cove )

Age: 35

Cause: Assault – Murdered with a Cutlass

Event location: ?

Event date: 26 August 1803

Funeral date: ? ? ?

Funeral location: ?

Funeral Parlour:

Buried at: the Old Sydney Burial ground. ( the site of the present Sydney Town Hall )

Body exhumed ( to make way for the Town Hall building ) and, allegedly, moved to Rookwood Cemetery.

Rookwood having no known records of the body’s location nor that of the Headstone

Memorial located at: ?

[alert_green]JOSEPH IS mentioned on the Police Wall of Remembrance[/alert_green]

[divider_dotted]

FURTHER INFORMATION IS NEEDED ABOUT THIS PERSON, THEIR LIFE, THEIR CAREER AND THEIR DEATH.

PLEASE SEND PHOTOS AND INFORMATION TO Cal

[divider_dotted]

May they forever Rest In Peace

[divider_dotted]

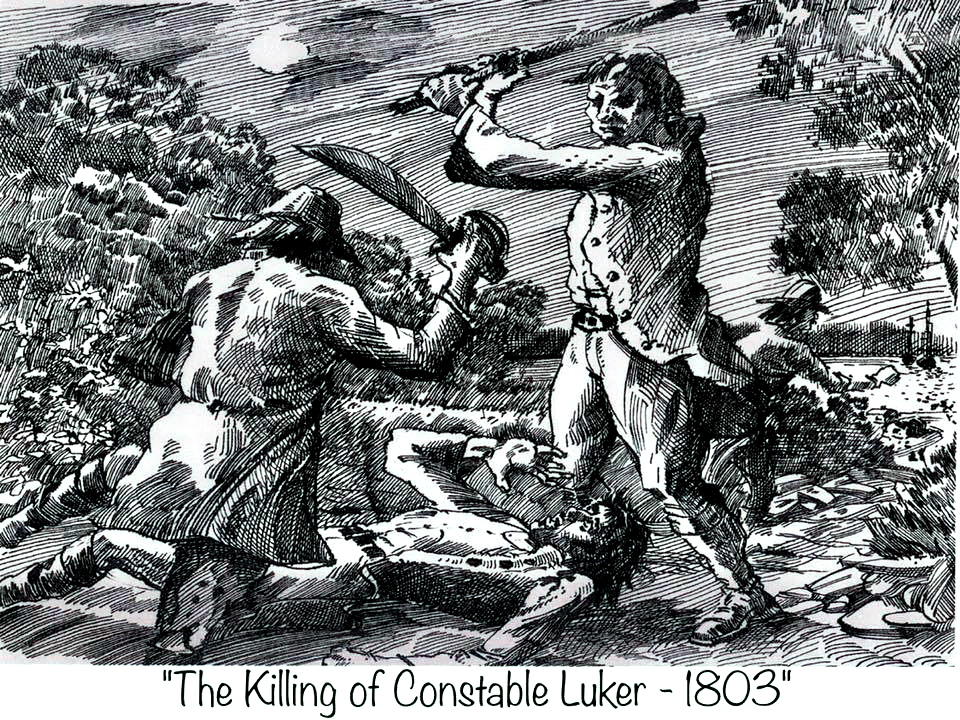

On the night of 25/26 August, 1803 Constable Luker was patrolling Back Row East, Sydney Town. His intention that night was to endeavour to capture a number of burglars who had recently committed several offences on homes in the area. In the early hours of the morning, during his patrol near Mary Breeze‘s dwelling (where an offence had been committed earlier that night) Constable Luker was set upon by a group of offenders and beaten to death. He suffered horrific head wounds and when found had his cutlass guard embedded in his skull. Another constable, Isaac Simmons, was strongly suspected of the murder however this allegation was never sustained, although he was almost certainly guilty. For the offences of stealing and Luker‘s murder Joseph Samuels was sentenced to death (commuted when three attempts to hang him failed) and John Russell was acquitted. Constables Isaac Simmons and William Bladders were both also found not guilty.

Australia’s first newspaper, the Sydney Gazette of Sunday 28 August, 1803 reported the story of Constable Luker’s murder and the ensuing enquiry in some detail, informing its readers that “Joseph Luker, a Constable, whose time of duty commenced at twelve o’clock, went off his post, as is conjectured, at or rather before daylight, with a design of examining the brush behind Back Row; but was shortly afterwards found on the edge of the road leading to Farm Cove, a breathless corpse, shockingly mangled, and with the guard of his cutlass buried in his brain”

The same newspaper reported on 6 November, 1803 that “A Grave-Stone has lately been erected over the head of the late unfortunate Luker, with an Inscription and Epitaph descriptive of the circumstances of his death”. The headstone, which was four feet (1.2m) in height, bore the following inscription (with an incorrect date of death).

Sacred to the Memory of

JOSEPH LUKER, Constable;

Assassinated

Aug. 19 1803. Aged 35 Years.

Resurrexit in Deo.

——————

My midnight Vigils are no more,

Cold sleep and Peace succeed;

The pangs of Death are passed and o’er,

My wounds no longer bleed.

But when my murderers appear

Before Jehovah’s Throne,

Mine will it be to vanquish there,

And theirs endure alone.

At the time of his death the constable was stationed in Sydney, at the eastern side of the settlement. He was an ex-convict who had been transported on the Atlantic in 1791, and had been a free man since 1796. He was the first Australian police officer to be killed on duty.

( Back Row East is now Phillip Street, Sydney and his beat included Mulgrave St and the site of the murder lies in the area bounded by Phillip Street, Hunter Street, Macquarie Street and Martin Place.)

[divider_dotted]

Luker ( ‘LUCAR’ ) was deported as a convict from Middlesex, England and disembarked at Port Jackson from the Atlantis in 20 August 1791 as part of the Third Fleet and aged around 26 years. It is also reported that Luker may have been aged 33 at the time of death.

Joseph ‘LUCAR‘ was tried at the Old Bailey along with James ROCHE on 8 July 1789 for stealing 84 lbs of lead from the home of George DOWLING on the night of 23 June 1789. The value of the lead was 10 shillings. Both ‘LUCAR‘ & ROCHE were convicted by Mr Justice Wilson, and sentenced to be transported for 7 years. Those that stole lead from roofs were known as ‘Bluey Hunters‘.

After spending 19 months in prison, they departed England on 27 March 1791 and arrived in Sydney on the Atlantic in August 1791.

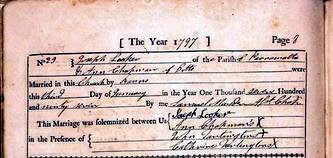

In a Church marriage register, on the 3 January 1797, ( *it is reported ) the man himself signed his name as Joseph LOOKER.

*Night Watch in Sydney Cove by Louise Steding

Joseph married Ann in Parramatta

http://www.abc.net.au/radio/programs/nightlife/rachel-franks/8479094 ABC Audio – the Nightlife with Philip Clark & Sarah MacDonald

[divider_dotted]

Marriage: LOOKER, Joseph to CHAPMAN, Ann. District: CB.

Registration # 155/1797 v 1797155 147A

Registration # 377/1797 v 1797377 3A

There is NO LUKER recorded between 01/01/1791 – 31/12/1830 in relation to marriages in NSW

There is NO LUCAR recorded between 01/01/1791 – 31/12/1830 in relation to marriages in NSW

Death: LOOKER, LUKER of LUCAR between 01/01/1790 – 31/12/1820.

The ONLY Death recorded in NSW BDM records in this date range is Joseph LOOKER who died 1803

Registration # 1817/1803 V 18031817 2A.

It would appear that LUKER is incorrect and the true surname of this man is LOOKER.

Cal

060318

[divider_dotted]

Writing the death of Joseph Luker: true crime reportage in colonial Sydney

http://www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/issue45/Franks.pdf

[divider_dotted]

Mystery solved in time for Police Remembrance Day

- The Daily Telegraph

- September 28, 2007

MORE than 200 years after Constable Joseph Luker was bashed to death while investigating a robbery near a Sydney brothel, the officer’s grave has finally been found again.

With the discovery of Constable Luker‘s original grave under Town Hall, the police have solved a Sydney mystery over the burial site of the first officer in Sydney to die on duty.

As the force prepares to commemorate fallen officers on Police Remembrance Day today, the story of Constable Luker’s final resting place can finally be told.

After years searching graveyard records, recent excavations under the Town Hall have revealed Constable Luker was buried in the Old Sydney Burial Ground, which was used from 1792 to 1820. Constable Luker’s grave was marked “assassinated“.

Records show the bodies of three policemen, including Constable Luker, were exhumed in 1869 when building began on the Town Hall site and they were interred at Rookwood Cemetery in Sydney’s west.

“It is important to police as an organisation that we ensure we honour and pay respect to those who have served before us and that is why we have continued to search for Joseph Luker’s burial place,” Police Commissioner Andrew Scipione said yesterday.

“Joseph Luker paid the highest price for protecting the citizens of the then fledgling colony. No organisation should ever forget the sacrifices of its staff.”

Sydney City Council found records showing another two officers, Constables Joseph Haynes and John Farmer, were buried on the Town Hall site but nothing is known about how they died.

Constable Luker was on a midnight patrol after a spate of burglaries near prostitute Mary Breeze’s brothel in Phillip St, then known as Back Row, east Sydney Town, in August 1803.

He had been beaten to death and his cutlass guard was wedged in his skull when his body was found near Macquarie St.

In one of the first scandals to rock the police, two of his colleagues were suspected but were never convicted.

A message to his killers was posted on his headstone at the Town Hall site telling them: “My midnight vigils are no more, Cold Sleep and Peace succeed . . . But when my murderers appear, before JEHOVAH’s Throne, Mine will be to vanquish there, And theirs endure alone.”

The 35-year-old was a convict who served seven years transportation before joining a fledgling police force.

Mr Scipione urged people to wear a blue ribbon on the right-hand side of their shirt today to show support for police. He said remembering lost officers was a way to offer continued support and comfort to their families.

“It means we will never forget their courage and sacrifice,” he added.

[divider_dotted]

Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), Saturday 23 May 1931, page 9

A STORY OF 1803.

“The Man They Could Not Hang.”

(BY W.R.S.)

The fatal legend “Death” appears with lamentable regularity at the foot of recorded proceedings of the Australian Criminal Courts in the concluding years of the 18th century, but as will later be shown, pardons and remissions were as frequently granted by subsequent Governors, as they were by Phillip at the beginning of the settlement in Sydney. Remembering the harshness of the Criminal Code, one is repelled by documents which denote the sacrifice of life for relatively trivial offences, but the extraordinary developments of the case recorded here, which are probably unique in actual human experience, bring it within the historic purpose of the present articles.

A BURGLARY AND A MURDER.

A long series of documented records of evidence before the Lieutenant-Governor in the Court of Criminal Jurisdiction led the writer to follow up the sequel to the trial of a number of persons charged with burglary and murder, which was narrated in the Sydney “Gazette” of October 2, 1803. Reducing the story of the crime from a pile of depositions in the possession of the Supreme Court, it appears that one night in August, between 7 and 8 o’clock, the dwelling house of a settler named Breeze was entered, and a desk containing jewellery, money, and valuable documents was removed. The matter was promptly reported to the Chief Constable, who stationed watchmen through the night in the bush at the back of the dwelling. One of the watchmen, Joseph Luker, came on duty at midnight, and at once set out on a patrol. Early in the morning the desk was found, and not far away the body of Luker, who had been brutally murdered. So fiercely had he been attacked that the guard of his cutlass was found imbedded in his brain. The gruesome discovery caused horror throughout the settlement. The Sydney Militia Corps were called to arms, and blockaded every avenue of escape from the town, and frantic search for the assassins began, every officer, military or civil, including the Lieutenant Governor, joining in the hunt.

Suspicion was at first attached to a man named Bladders, who was charged and held, but before long others were arrested. Many witnesses were examined, the Court adjourned from day to day, and excitement in the town reached fever heat.

EIGHT SENTENCED TO DEATH.

The arrest of Bladders followed a finding of a Coroner’s Court composed of twenty “very respectable Inhabitants.” The boon of trial by jury had not yet been conferred on the colony, though agitation for the reform was growing amidst the free population, and the tribunal charged with the final jurisdiction was still of the military type, created by letters patent at the landing. As the facts were sifted, suspicion swung steadily in the direction of four men, Joseph Samuels, John Ruffell, Bladders, and Isaac Simmonds, and the final solution appeared in sight when Samuels, while denying the murder, confessed the theft, and assisted the Government officials to recover portion of the loot which had been buried in the bush. Ruffell was also charged with the theft, but after trial was acquitted. The more serious charge of wilful murder was preferred against Isaac Simmons and William Bladders, but the Court were of the opinion that the evidence offered by the Crown was insufficient to convict, so that they also were discharged.

The sitting had been a sensational and protracted one, and the Court passed sentence of death on no fewer than eight persons. Immediately after the trial Governor King exercised his prerogative and remitted the penalty, in three cases, to transportation for life. Samuels and another man named James Hardwick, who had been sentenced to death for theft of clothing, were removed to gaol for immediate execution. The convictions took place on September 23, a Friday, and the executions were ordered for the following Monday. The gallows at the time had been removed from the original site in the camp to Castle Hill, and the condemned prisoners were conveyed from the city prison overnight to a gaol at Parramatta.

REPRIEVED UNDER THE GALLOWS.

An echo of the profound sensation created by the hanging of Samuels is to be found in a description written by a reporter of the Sydney “Gazette,” whose feelings are alternately swayed by horror, pity, and religious fervor.

“The two men were brought up to the scene of execution in a cart at 9 o’clock in the morning, and both conducted themselves with becoming decency. The chaplain, the Reverend Samuel Marsden, at once commenced his ministrations with Hardwick, while Samuels, who was a Jew, was being prepared by a person of his own profession. Upon leaving Hardwick, the chaplain walked over to Samuels, who was urged to purge his conscience at the last moment by revealing his part in the crime. Prominent in the multitude of spectators surrounding the hill was Simmonds, who had been brought in custody from George’s Head to witness the lawful end. At first Samuels declined to make any statement, declaring that he had taken an oath, in Hebrew, with Simmonds, while in prison, to preserve secrecy and silence. Yielding to persuasion, however, he afterwards stated that Simmonds had told him that the constable had surprised him with the desk belonging to Mary Breeze, and that he had ‘knocked him down and given him a topper for luck.’ Also, that the tragedy would not have happened if the whereabouts of the stolen money had not been concealed from him. It is not to be wondered at,” says the “Gazette,” “that testimony like that, proceeding from the lips of a dying man, whose only probable concern was to ease the burden of his conscience in the hour of death, should at once remove all doubt, if such remained, as to Simmonds’s guilt, and the feelings of the multitude broke forth in invective.”

At 10 o’clock the two criminals reascended the cart, and when just about to be launched into eternity, a reprieve for James Hardwick arrived, and was announced by the Provost Marshal.

THE ROPE BREAKS THREE TIMES.

The “Gazette” proceeds: “Samuels devoted the last awful minute allowed him to earnest and fervent prayer. At last the signal was given, and the cart drew from under him, but by the concussion, the suspending rope was separated at about the centre, and the culprit fell to the ground, on which he remained motionless, face downwards. The cart returned, and the criminal was supported on each side until another rope was obtained, in lieu of the former one. He was again launched off, but the line unrove, and continued to slip until the legs of the sufferer trailed along the ground, the body being only half suspended. All who beheld the man’s protracted suffering were profoundly moved.

To every appearance lifeless, the body was again raised and supported on men’s shoulders while the executioner prepared anew his work of death. The noose was adjusted and the body gently lowered, and when left alone again, fell prostrate to the earth, the rope having snapped off short, close to the neck.

PROVOST-MARSHAL IN TEARS.

The scene which followed numbed the writer’s powers of description. Emotion could no longer bear repression, and the Provost Marshal, he tells us, charged with humanity sped off to his Excellency’s presence to plead for mercy. The success of his mission completely overcame him. A reprieve was announced and, adds the “Gazette,” “if mercy be at fault, it is the dearest attribute of God, and surely in heaven it may find extenuation.” Samuels, it appeared, when the Provost Marshal arrived with the tidings, which diffused gladness throughout every heart, was incapable of participating in the general satisfaction.

The half-strangled prisoner slowly recovered and uttered incoherent remarks, and when fully restored to consciousness, by surgical aid, had no recollection of what had passed. The “Gazette” concludes its account: “And may the hateful remembrance of these events direct his future course.”

A test was made of one of the ropes which failed at the execution. It was found to be defective in the short section where the break occurred, the remaining length, even with two strands severed, being capable of supporting three 56lb weights.

( This remarkable miscarriage had an immediate effect, in ways which will be described in a further article on primitive punishments, suggested by a somewhat mysterious document discovered in the Court archives. )

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/16780083

[divider_dotted]

Australia’s first newspaper, the Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser of 28 August, 1803 reported the story of Constable Luker’s murder in some detail.

“ROBBERY.

On Thursday night, between the hours of seven and eight, the dwelling-house of M. Breeze, at the corner of Back Row, was broke into, and robbed of a Desk containing £24 or thereabouts in cash, viz. £12.10 in Dollars, 3 Guineas, 3 Pieces of Gold, value £2 each, and some Copper Coin; as also an Order on Captain Bishop, drawn by Captain Park in favour of Mary Breeze for £20 and an Agreement for the Purchase of her house.

The Robbery was effected by entering the premises at the back during her absence from home: the frame of the door was broke by means of a prise, or purchase; and although a quantity of wearing apparel and other property lay open in the bed-room, yet nothing but the desk was taken away. Information being immediately lodged with the Chief Constable, he posted watchmen in the back brush during the greater part of the night; the vigilance of one of whom, we have too ample reason to conclude, occasioned his most barbarous and dreadful murder.

Joseph Luker, a Constable, whose time of duty commenced at twelve o’clock, went off his post, as is conjectured, at or rather before daylight, with a design of examining the brush behind Back Row; but was shortly afterwards found on the edge of the Road leading to Farm Cove, a breathless Corpse, shockingly mangled, and with the guard of his cutlass buried in his brain; the sheath lay near the body; and his hat more than 20 yards distant. The wheel of a barrow was found near the spot, the carriage of which was traced to the yard of Sarah Laurence, at the opposite corner of Back Row, whose Skilling was inhabited by persons on whom suspicion of the Robbery had fallen. The carriage of the Barrow appeared to be stained with blood: from which and other circumstances William Bladders, alias Hambridge, was immediately apprehended, with several other suspected persons.

The velocity with which the necessary measures of Enquiry were adopted, could only be equalled by the Public Anxiety to discover the Perpetrators of the inhuman act. The New South Wales Corps were out under Arms, and blockaded the Town at every avenue, while the strictest search was made throughout; and all persons of suspicious character were thereby secured, and brought before the Coroner’s Inquest, which assembled between the hours of nine and ten.

John Harris, Esq. Surgeon of the New South Wales Corps, strictly attended the Enquiry, and inspected the Body; as did also Thomas Jamison Esq. Surgeon General, and Messrs. Mileham and Savage, Assistant Surgeons to the Colony.

On the head of the deceased were counted Sixteen Stabs and Contusions; the left ear was nearly divided; on the left side of the head were four wounds, and several others on the back of it. The wretch who buried the iron guard of the cutlass in the head of the unfortunate man had seized the weapon by the blade, and levelled the dreadful blow with such fatal force, as to rivet the plate in the skull, to a depth of more than an inch and a half…”

At the time of his death the constable was stationed in Sydney, at the eastern side of the settlement. He was an ex-convict who had been transported on the Atlantic in 1791, and had been a free man since 1796. He was the first known Australian police officer to be killed on duty, and as such he is listed in the official New South Wales Police Honour Roll.

[divider_dotted]

Joseph Luker (c. 1765 – 26 August 1803) (also spelt Lucar and Looker) was a Sydney foot police officer who was recorded as the first police officer to be killed on duty in Australia. It is Australia’s oldest cold case.[1]

Luker had been deported as a convict from Middlesex, England and disembarked at Jervis Bay from the Atlantis in 1791, as part of the Third Fleet after a voyage of 146 days. In 1796, Luker was declared a freeman and became a police constable.

On 26 August 1803, Luker was on a routine night patrol of Back Row East, now Phillip Street, Sydney, where a series of robberies had occurred.

When his body was found the next day, he had suffered 16 horrific head wounds, with the guard of his cutlass embedded in his skull.

Four men later faced court for his murder – Joseph Samuel, Isaac Simmonds, Richard Jackson and James Hardwicke. Three were acquitted, as were two fellow constables. Samuel was originally sentenced to death for his role in a robbery, but this was commuted to life imprisonment after three attempts to hang him had failed. Simmonds was strongly suspected of involvement in Luker’s death, but this was never sustained in court.

Luker is now commemorated in the National Police Memorial at King’s Park, Canberra.

References

- First Officer Killed on Duty in In the Line of Duty: A Special Supplement Commemorating National Police Remembrance Day and the Dedication of the National Police Memorial, Canberra Times, 29 September 2006, page 7 a&b.

- Specific

1963-,, Steding, Louise, (September 2016). Death on night watch : Constable Joseph Looker : New South Wales, 1803. Steding, Gerald,. Camden: In Focus Press. ISBN 9780992574505. OCLC 965890297.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Luker

[divider_dotted]

2 Comments