Brett Clifford SINCLAIR

Brett Clifford SINCLAIR – V.A.

( late of Eastwood )

New South Wales Police Force

[alert_yellow]Regd. # 21771[/alert_yellow]

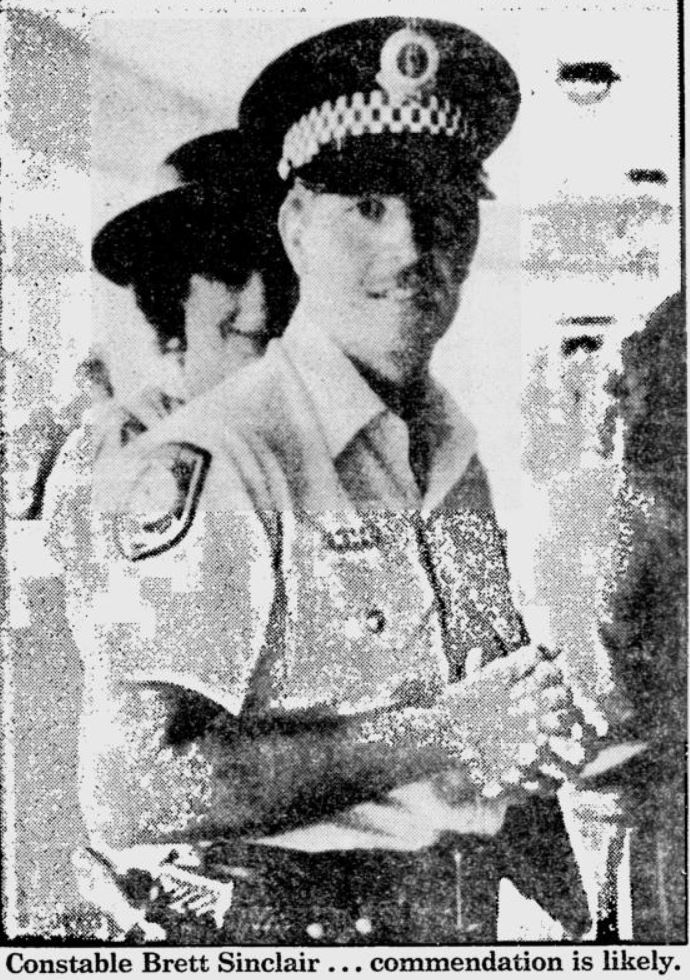

Rank: Constable

Stations: ?, Parramatta HWP

Service: From 8 December 1984 to 25 October 1988 = 3+ years Service

Awards: Commissioner’s Valour Award for Bravery and Devotion to Duty

Born: 12 March 1959

Died on: Tuesday 25 October 1988

Cause: Murdered – by motor vehicle

Event location: Jeffrey Ave, Nth Parramatta

Age: 29

Funeral date: Friday 28 October 1988 @ 11am

Funeral location: St Anne’s Anglican Church. Church Street, Ryde.

Buried at: Cremated

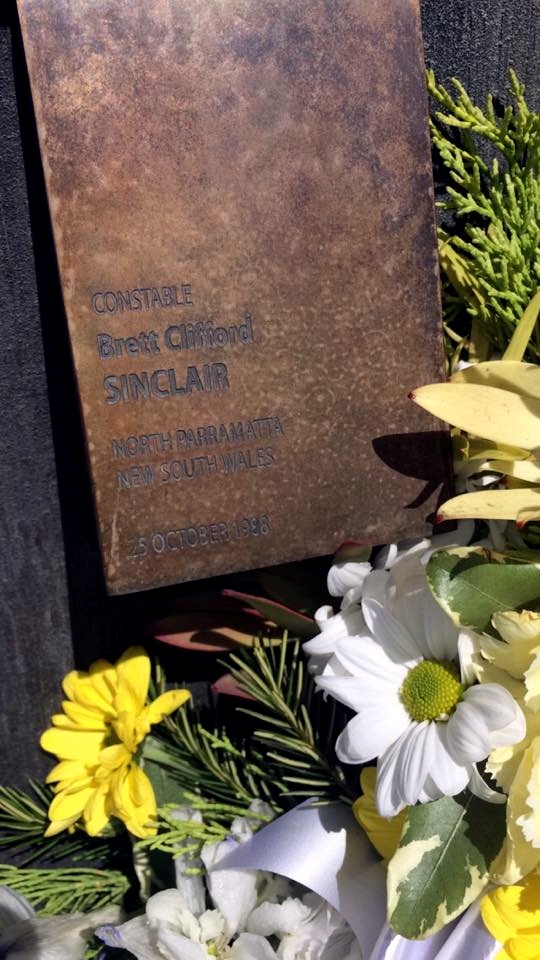

Memorial at: National Police Wall of Remembrance, Canberra &

Parramatta Police Station, NSW.

[alert_green]BRETT IS mentioned on the Police Wall of Remembrance[/alert_green]

Touch plate at the National Police Wall of Remembrance, Canberra

[divider_dotted]

FURTHER INFORMATION IS NEEDED ABOUT THIS PERSON, THEIR LIFE, THEIR CAREER AND THEIR DEATH.

PLEASE SEND PHOTOS AND INFORMATION TO Cal

[divider_dotted]

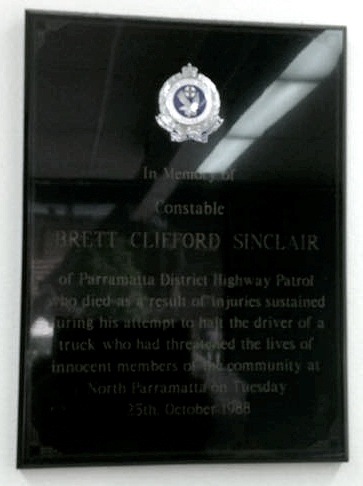

Murdered On Duty 25 October 1988.

” Our Mate “

In Memory of Constable Brett Clifford Sinclair of Parramatta District Highway Patrol who died as a result of injuries sustained during his attempt to halt the driver of a truck who had threatened the lives of innocent members of the community at North Parramatta, Tuesday 25th October 1988.

BELOVED HUSBAND, SON AND BROTHER.

12-3-1959 – 25-10-1988

SADLY MISSED

[divider_dotted]

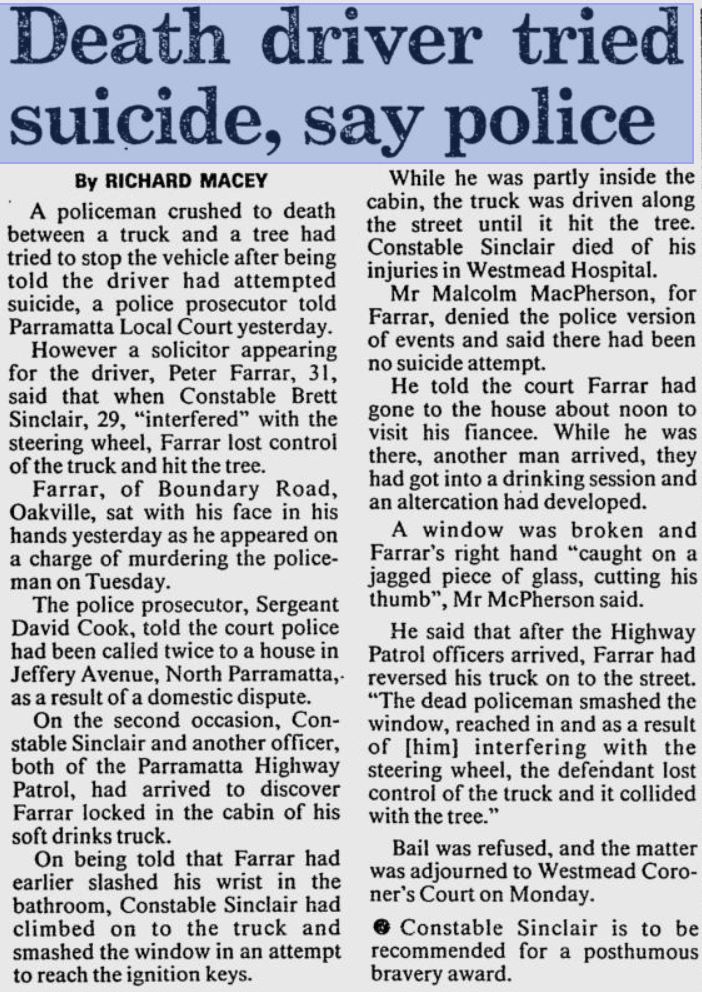

About 5.50pm on 25 October, 1988 Constable Sinclair suffered severe head and internal injuries at North Parramatta whilst attempting to arrest an offender following a domestic dispute. Earlier, police had been called to assist ambulance officers at the disturbance in Jeffrey Avenue. The offender, who was bleeding from the arm, had locked himself in his truck. While Constable Sinclair and Constable Cummins spoke with him, he continually threatened them while revving up his truck engine. As the police approached the offender wound up his window. The police then smashed the window and attempted to remove the driver from the cabin of the truck. With both police standing on the step of the truck, the offender began to drive along Jeffrey Avenue.

Constable Cummins was able to get off the step, but due to his falling to the roadway, was unable to assist his colleague.

The truck’s speed increased with Constable Sinclair still partially inside, and partially outside, the cabin. The offender then drove across the roadway where the vehicle collided with a tree, crushing the constable.

He was conveyed to the Westmead Hospital where he died a short time later. Constable Sinclair was awarded the Commissioner’s Valour Award for Bravery and Devotion to Duty.

The constable was born in 1959 and joined the New South Wales Police Force on 8 December, 1984. At the time of his death he was attached to the Parramatta Highway Patrol.

[divider_dotted]

Pre Police, Brett worked for QANTAS

[divider_dotted]

The Sydney Morning Herald 27 October 1988 p36

The relatives and friends of the late BRETT CLIFFORD SINCLAIR (Cons NSW Police Force), of Eastwood, are invited to attend his funeral, tomorrow (Friday), to leave St Anne’s Anglican Church. Church Street. Ryde., 11am.

At the conclusion of the service the funeral will leave for the Northern Suburbs Crematorium.

DIGNIFIED FUNERALS.

FDA -NSW. FIVE DOCK.

713 1911

https://www.newspapers.com/newspage/120541199/

[divider_dotted]

A series of gunshots fired at close range killed 26-year-old police officer Glenn McEnallay in his highway patrol car after he responded to a report of a stolen car in Matraville in March 2002.The man who pulled the trigger, Sione Penisini, was sentenced to 36 years in prison, but his accomplices escaped with much shorter sentences after they pleaded guilty to manslaughter. A public outcry followed and the murdered officer’s father, Bob McEnallay, described the seven-year jail term handed to one of them as “an absolute bloody joke”.

But this week he made it clear he does not believe his son’s life was worth more than that of any other citizen. He says the state government’s plan to introduce mandatory life sentencing for people who murder police is unfair to other victims of serious crime. Bob McEnallay says the life of his surviving son, Troy, not a police officer, should not be valued less than that of Glenn. He believes there should be a minimum sentence for murder, regardless of who the victim is.

“I wouldn’t like to think my son’s case would attract more attention from the courts than some other citizen,” he says. “I know the [government’s] intentions are good, but I would rather see a system where the maximum possible sentences for murder are issued for any citizen who is murdered.”

The NSW Attorney-General, Greg Smith, says the bill to be introduced in Parliament this week was developed in response to the murder of police officers David Carty in 1997 and Glenn McEnallay. His office confirms the new law will not apply to accessories to murder, such as the Taufahema brothers who were involved in the McEnallay killing. The new law will mean only the murderer would serve the term of his natural life in prison.

The Premier, Barry O’Farrell, says the Coalition has been committed to the policy since 2002 and will “ensure that those who murder police officers spend their lives behind bars”.

But in 2010, Mr Smith denounced those who called for mandatory sentencing as “rednecks”, who were indulging in a “law and order auction”. He now says police killings are an exception. “The murder of a police officer is a direct attack on our community and warrants exceptional punishment,” he says. “It sends a serious message of support to our police, but I hope it is never used.”

Mr Smith prosecuted two trials in relation to the murder of Carty and he conducted the committal hearing. “I gave my blood, sweat and tears to that case in honour of that policeman. I then appeared in the appeals to the Court of Criminal Appeal and the High Court, both of which were dismissed,” he says.

Mr McEnallay says he can appreciate the support of John Carty, David’s father, for the new law, but does not agree that police officers should be treated differently. “I am very pro-police,” McEnallay says. “But I just hope some good legislation comes out of this for everybody.”

Mary Cusumano, whose husband Angelo was shot dead in his Penshurst computer store 15 years ago, leaving her to raise four children on her own, says she is angry with the new law. This week she learnt her husband’s murderer is up for parole.

“It just infuriates me,” she says. “My husband was a wonderful human being and he served his community. It is as if the government is saying his life is worth less than somebody else’s.

“With all due respect to the police, they make a choice to enter that career, with all the risks it involves. They are armed, my husband wasn’t. My husband never thought he would go to work and that a person would put a rifle to his head.”

Martha Jabour, who represents the Homicide Victims Support Group, says the new law will divide families. “If the government is thinking of making it mandatory life, why not mandatory life for every life. I cannot say that one occupation is far more worthy than the life of a nurse or a vulnerable child.

“If my son was murdered I would want his murderer to get life, but my son isn’t a police officer.”

The vice-president of the Victims of Crime Assistance League, Howard Brown, says ambulance and other emergency service personnel will not be treated equally under the new law. “It is a dangerous piece of legislation because it has not been well thought out,” he says. “We are told by the judiciary and by politicians that everyone is treated equally before the law. But for some reason they have decided to place police above everyone else, including judges.”

Mark Findlay, a professor of criminal justice at the University of Sydney, says it is “a pity that the new government’s legislative agenda for criminal justice should be opening with what is largely something for appearances”.

“The murder of a police officer should be condemned. But if the families of police officers are meant to be comforted by this proposal it would only be at the level of retribution,” he says. “There is no convincing evidence that mandatory life sentences have any significant deterrent effect on those who kill police officers in the circumstances in which such murders take place.”

The Greens MP David Shoebridge says mandatory life sentencing has not worked in other countries and does not produce a reduction in crime. The US Sentencing Commission delivered a report to Congress nearly 20 years ago denouncing mandatory minimum sentences. In its 1991 report, it said mandatory sentencing failed to improve public safety or deter crime.

Nicholas Cowdery, who retired last month as the head of the Department of Public Prosecutions, was involved in the prosecution of McEnallay’s killers. He says the new law “appears to be a purely political exercise to in some way satisfy an obligation to the NSW Police Association.

“I say that because there is no present criminal justice need for this legislation. There are no miscarriages of justice or anomalies that have occurred in the past that justify departure from the existing law. The present law is well capable of imposing a suitably severe penalty on a person who murders a police officer or a person in other categories of employment which have an increase in risk of harm attached to them.”

The existing law allows judges to impose a sentence of natural life for murder, and about 50 people are serving that sentence.

Death on duty

NSW police killed since 1980

1980 Sergeant Keith Haydon, shot at Mount Sugarloaf.

1984 Constable Pashalis Katsivelas, shot by an escaping prisoner at Concord.

1986 Sergeant Paul Quinn, shot during a pursuit at Perthville.

1988 Constable Brett Sinclair, died from injuries while making an arrest in North Parramatta.

1989 Constable Allan McQueen, shot while making an arrest in Woolloomooloo.

1995 Senior Constables Peter Addison and Robert Spears, shot at Crescent Head.

1997 Constable David Carty, stabbed outside a Fairfield hotel.

1998 Constable Peter Forsyth, stabbed while making an arrest in Ultimo.

2001 Senior Constable James Affleck, deliberately run over as he set up road spikes to stop a stolen car in Campbelltown.

2002 Constable Glenn McEnallay, shot at Matraville after a pursuit.

Source: Hansard

[divider_dotted]

Crimes Amendment (Murder of Police Officers) Bill 2007

Reverend the Hon. Dr Gordon Moyes:

OBJECTIVES:

The object of the Crimes Amendment (Murder of Police Officers) Bill is to amend the Crimes Act 1900 to provide that compulsory life sentences are to be imposed by a court on persons convicted of murdering police officers. A compulsory life sentence is to be imposed if the murder was committed while the police officer was executing his or her duties or as a consequence of, or in retaliation for, actions undertaken by any police officer.

COMMENTS:

The tragic suicides of young officers, the attempted suicide of a senior officer and the recent very public breakdown of another young officer are reminders to us all of how tough it is to be a police officer in 2007. Every day police officers kiss their loved ones goodbye and go to work, knowing the dangers that may confront them. Supporters of the bill argue that those convicted of murdering police officers do not deserve another chance to be free members of society. Murdered police officers do not have another chance at life and their killers should not have another chance at freedom. I would also mention, however, that it is grieving families, aside from those convicted and those who are murdered, who endure the pains of such actions.

Since 1995 at least 18 police officers have died as a result of duty-related incidents. These include five who were murdered in the course of carrying out their duty. Another four police officers are assaulted every single day, as a previous speaker has mentioned. It is unacceptable that people involved in some of these murders are now enjoying their freedom. That should change and this bill seeks to effect that change. There can be no clearer justification for this legislation than the fact that, since 1980, 11 officers have lost their lives as a result of the actions of offenders who have attacked police executing their duty to protect the community.

They are Sergeant Keith Haydon, shot by an offender on 24 November 1980; Constable Pashalis Katsivelas, shot by an escaping prisoner on 4 April 1984, from recollection, at Concord Hospital—a probationary constable, I am reminded; Sergeant Paul Quinn, shot by an offender following a pursuit on 30 March 1986; Constable Brett Sinclair, from injuries sustained whilst effecting an arrest on 25 October 1988; Constable Allan McQueen, shot whilst effecting an arrest of a man breaking into a motor vehicle only a few hundred metres from where we are now sitting on 5 May 1989; Senior Constable Peter Addison and Senior Constable Robert Spears, shot by an offender at Crescent Head as they got out of their vehicle to enter a home on 9 July 1995; Constable David Carty, stabbed during an affray in Western Sydney on 18 April 1997; Constable Peter Forsyth, stabbed whilst effecting an arrest on 28 February 1998; Senior Constable James Affleck, struck by a motor vehicle whilst deploying road spikes to stop a stolen car on 14 January 2001; and Constable Glenn McEnallay, shot by an offender at Matraville following a pursuit on 3 April 2002.

In the light of recent decisions relating to the murders of David Carty and Glen McEnallay it is apparent that there is strong community support for police and for the introduction of measures to deter offenders from assaulting and killing members. The bill is predicated upon a belief that police officers are rightfully owed a measure of protection by the community. This so for at least two reasons. First, police officers place themselves in positions of risk on behalf of the community. Second, an attack on a law enforcement officers strikes at the very core of our system of democratic government. Those who seek to harm the persons responsible for the enforcement of laws passed by our Parliament should be subject to special punishment.

That principle is already recognised in the Crimes Act. Section 58 of that Act imposes a higher maximum jail penalty for the offence of common assault of a police officer than is imposed for the same offence against an ordinary civilian. Indeed, the relative maximum penalties are five years and two years respectively. Surprisingly, and anomalously, the principle is not carried through by the Crimes Act to apply to more serious assaults that in fact inflict injury or permanent damage to officers. When police officers are in uniform on duty or have recalled themselves to duty they put themselves forward when others step back. They put themselves in danger and do so to protect you and me and citizens of the State. The law should recognise that to murder a police officer is a serious crime in this State. The Parliamentary Secretary for Police, who led for the Government, said:

The Government wants people who murder police officers to rot in prison; we have never resiled from that position.

Today Government members have the opportunity to stand by this commitment and that of former Premier Carr. He said:

I want those who murder police officers to go to gaol forever. I want those who murder police officers to go to the dingiest, darkest cell that exists in a prison system …

Government members have the opportunity to vote for this legislation, which will mean that those who murder police officers will rot in prison. There are certainly some contentious provisions that merit further examination. However, there are two aspects of this bill that do concern me. The first is: Is there any evidence that the likelihood of a compulsory life sentence would have any deterrent effect? I ask whether a compulsory life sentence can achieve reduced recidivism and increased rehabilitation in our society. Can a compulsory life sentence stop future acts of violence? Is the life of a police officer more valuable than the life of anyone else, such as a doctor treating a patient, teachers or others in the community?

If honourable members consider any aspect of my speech today I ask them to reflect on this one point: I remind them that the stark account of prison life presents powerful challenges in our liberal democracy. During my whole life, from the time I was a parole and probation officer as a young man through to all my years at Wesley Mission, I have visited numerous prisons around the country. In fact, at different times I have been detained in her Majesty’s finest. Most of them are characterised by routine, regulation, boredom and depression associated with serving a long-term sentence. They are also characterised by claustrophobia, noise, chaos and the real risk of being compelled to inhabit a very violent world, including not only other prisoners but also others who enter the prison. Inmates that I have talked to over the years inevitably possess low intelligence quotients or have suffered brain damage, frequently from extensive alcoholism, and mental illness. Critical criminologists and sociologists have long since documented the squalor and brutality associated with incarceration. Even in today’s society, public complacency generally surrounds the plight of the incarcerated.

The growing fear of crime, fuelled at least partially by the media, and the frustration with the seeming lack of positive results of rehabilitation provide public support for hardened policies. This trend has become amplified by the rhetoric of politicians who have found that being tough on crime is an unbeatable popular issue.

CONCLUSION:

However, with all of that said, with the limitations of our current prison system and acknowledging the absolute futility of long-term incarceration of individuals, there is no question in my mind that the Crimes Amendment (Murder of Police Officers) Bill is needed. I commend the bill to the House.

http://www.gordonmoyes.com/2007/11/16/crimes-amendment-murder-of-police-officers-bill-2007/