The 1927 Tahiti-Greycliffe Disaster

Sydney Harbour’s greatest maritime disaster occurred on 3 November 1927, when the Royal Mail Steamer Tahiti collided with the Watsons Bay-bound ferry Greycliffe off Bradleys Head. The tragedy shocked Sydneysiders for it’s unsurpassed violence and dispassionate choice of victims; in mere seconds, forty people, aged from just two to 81, were swept to their deaths, whilst dozens more were injured.

At the time of writing [late 2002], the Tahiti-Greycliffe Disaster remains the deadliest shipping accident ever to have occurred on Sydney Harbour. Whilst losses were minimal in comparison to some of the more infamous maritime accidents in history, the tragedy stunned people because of its swiftness and horror. There was no storm and no swell. Visibility was clear and it was a fine, sunny afternoon.

Greycliffe took a broad cross section of the community to the bottom of the harbour with her. Amongst them were six school children, aged eleven to fifteen, and the Science Master of Sydney Boys’ High School. Three doctors went to their deaths, one in the N.S.W. Prisons Service, another the Chief Quarantine Officer of N.S.W. and the third a Surgeon Lieutenant-Commander in the Royal Australian Navy. Three further Navy personnel were drowned, as well as seven tradesmen from Garden Island Dockyard. Six holiday-makers from N.S.W. and Victoria also met their deaths alongside Australia’s first female pilot and a six-times Mayor of Leichhardt. An architect, a retired Master Mariner, three retired gentlemen and seven housewives completed the sad list.

She was the regular 4.14 p.m. run from Circular Quay to Watsons Bay, the northern-most suburb of Sydney’s leafy Inner South Head. Nicknamed ‘The School Boat’, this particular trip had earned its name for the city school children the ferry brought home each afternoon.

Typical of the Sydney ferries of her day, Greycliffe was a wooden, doubled-ended vessel with a wheelhouse, rudder and propeller fitted at each end. Weathered white bulwarks ran the length of the 125-foot vessel at deck level, encircling varnished wooden outdoor seats. These in turn surrounded segregated men’s and women’s saloons; the men’s forward, over the boiler room, and the women’s aft, over the engine room.

Above them lay an upper deck, where, like the main deck, both inside and outside seating was provided. At each end of this deck stood the wheelhouses, identical in every detail, except for the ferry’s bell which was mounted on the port side of one.

Greycliffe slipped by Mrs Macquarie’s Chair on her starboard side, then Fort Denison to port, and heaved to at Garden Island ferry wharf. The ferry’s propeller churned up the water as it fought against her forward motion to slow her arrival at the dockyard pontoon. As she heaved to, the gangways were run out to greet the sea of brown suits and white uniforms. At this time of day, the wharf was always overflowing with Dockyard workers awaiting ferries to take them home to different parts of the harbour after their day’s work.

At her wheel stood Captain William Barnes. At 52, Barnes had been plying the harbour some 30 years and knew Port Jackson well. Although he had skippered Greycliffe on and off for ten years, he was not her usual Master; he only took the helm on Wednesdays and Thursdays when the regular Master took his days off. Today was such a day.

As the ferry departed Garden Island, Captain Barnes glanced over his shoulder through the forward wheelhouse’s rear port window and over the roof of the upper deck cabin. Seeing nothing, he turned the wheel two points to port and increased speed. Behind the little ferry, in the distance now, the new harbour bridge was under construction. Barnes adjusted his course again and steered for the navigation light 100 yards north of Shark Island.

It was a beautiful afternoon on the harbour. It was clear and sunny, and, although the westerly breeze was too light to pick up a chop, it was fresh enough to keep the temperature at a comfortable 71°F. Ahead of him, Barnes could see the ferry Woollahra coming towards him from Nielsen Park on the return leg of the same route. Around Bradleys Head, a tug was also coming in his direction, towing a small barge.

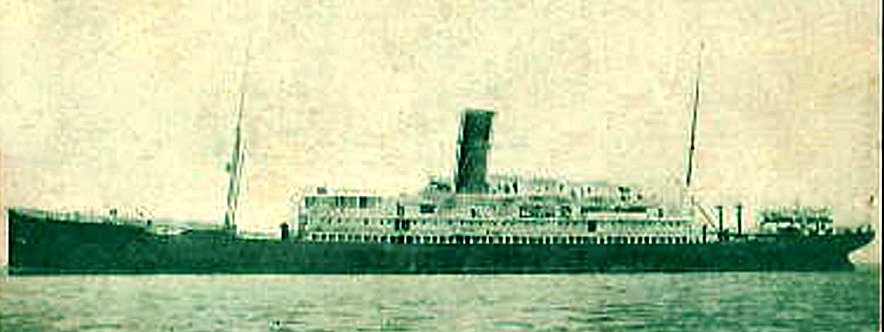

To his rear, however, unbeknown to Barnes, Greycliffe was also being approached by the Union Steamship Company’s graceful passenger liner, R.M.S. Tahiti. Bearing over 300 passengers and crew bound for New Zealand and the United States, the impressive-looking vessel crossed Circular Quay and routinely sounded the horn as a warning to other harbour traffic.

Displacing almost 7600 tons, she measured some 460 feet in length. Her gleaming olive-green hull stood in stark contrast to her shining white above-deck cabins. A neat row of covered lifeboats hung from davits along the length of the upper-most deck on each side, and a single, plump red funnel with a black top stood above them, amongst a clutter of ventilators.

A buff-coloured mast stood at each end of the vessel. They were supported by a complicated system of rigging, each almost a work of art in itself. They were surrounded by derricks which serviced her generous below-deck cargo holds, whilst a small crow’s-nest was perched about a third of the way up her foremast.

On the bridge, Captain Basil Aldwell casually chatted with the pilot assigned to the vessel that afternoon, Captain Thomas Carson. The two Captains had known one other for some ten years and had an amicable respect for each other. They shared the bridge with the helmsman, Quartermaster Roderick McLeod, and with the Third Officer, Harold Litchfield, who was stationed by the engine-room telegraphs.

A charming Scotsman of personable nature, Carson was in his late forties and beginning to grey. Although some nine years Aldwell’s junior, the Master Mariner had almost twenty years experience as a Pilot and was previously at sea, having circumnavigated the globe under both sail and steam. His career with the Pilot Service began in Sydney, but he subsequently spent several years piloting in Newcastle. He returned to Sydney in 1923, and had been stationed at Watsons Bay ever since.

Aldwell was a Union Steamship man who had spent almost his entire career with the Company. A Master Mariner with over 30 years experience at sea, the 57-year-old Englishman was by no means new to Tahiti. He first captained her in 1919 and, having been her permanent master since 1922, he felt quite at home on her bridge.

Only a relatively short distance away, just outside Sydney Heads, Carson’s duty to oversee Tahiti‘s navigation down the harbour would be done. There, as was the procedure, Carson would hand over command to the Captain, transfer to the pilot steamer Captain Cook II and return to the Pilot Station at Watsons Bay.

For Captain Aldwell, however, this was the point where the voyage began. Beyond the Port Jackson lay his distant ports of call; Wellington, Rarotonga, Papeete, and finally San Francisco.

Tahiti made a proud picture as she moved down the Harbour in the afternoon sunshine. Built in Glasgow in 1904, the 23-year-old steamer originally wore the name Port Kingston on her stern. When acquired by the Union Steamship Company in 1911, she was renamed Tahiti and put into the trans-Pacific passenger and mail service. Her career was interrupted during World War I when she served the Commonwealth as a troopship. Most of her luxurious furnishings were removed for the purpose, but she was returned to her original glory in the months after the War and resumed her former role in the Pacific early in 192.

Although the vessel afforded accommodation for over 500 passengers in three classes, as she slid down Sydney Harbour that afternoon she carried less than half that number. Out on deck, first class passengers lined the rails alongside second and third class passengers as they savoured a last long look at the city.

Carson ordered the engines to be put to ‘half ahead’ across Circular Quay and routinely sounded the horn. He ordered ‘full ahead’ as they passed Bennelong Point, and the ship began to increase speed as they swept past Fort Denison and approached Garden Island.

Aldwell and Carson surveyed the familiar scene around them while they chatted with each other. Both lived in Sydney and knew the harbour well. They noted the Watsons Bay-bound ferry, Greycliffe, which had just departed Garden Island, running down the harbour ahead of them, a few points off their starboard bow.

Department of Navigation regulations stipulated the course they must take down the harbour. Carson knew this meant his path would cross Greycliffe‘s before long but he felt confident the ferry was aware of his presence. He directed the helmsman to steer for the north end of Shark Island.

A little ahead of them, on their port side, the Circular Quay-bound ferry, Woollahra approached from the opposite direction. In moments, she would pass the liner down her port side. Carson kept a close eye on the two ferries, steering more-or-less parallel courses to take Tahiti between them.

To their rear, another ferry followed. Manly-bound Burra-Bra had left Circular Quay a few minutes after Tahiti swept past. Still picking up speed, the ferry was belching thick black smoke as she worked up to nine knots.

Rolling through Tahiti‘s wake, slightly to her port side, Burra-Bra‘s helmsman, Rupert Nixon, saw Woollahra coming directly for him. He ported his helm and moved to starboard, out of her way. Now squarely astern of Tahiti, and almost abreast of Fort Denison, he saw Greycliffe ahead, off the liner’s starboard bow.

Second Officer Gibson came onto Tahiti’s bridge as the vessel passed Garden Island, having gone to his cabin to change his coat for the evening ahead. He stepped inside just as Carson cried out in alarm. Gibson swung around to see Greycliffe steering a course which would surely bring her into collision with the liner.

Aldwell raced to the starboard wing of the bridge and froze. There was little he could do but watch whilst Carson barked orders. They had little immediate effect. At the speed the liner was doing, she would run several hundred feet before she would begin to turn away, let alone stop. Carson seized the lanyard to the funnel’s steam horn and pulled on it hard, twice.

Astern of them, aboard Burra-Bra, Rupert Nixon was just as helpless as Aldwell. Greycliffe kept on her course, apparently unaware of Tahiti‘s presence. He watched as the gap between the two vessels quickly diminished; Greycliffe raced in to meet Tahiti’s bow, like a magnet drawn to steel.

Aboard Greycliffe, inside the smoky Men’s Saloon, Fred Jones, known to many of the passengers as ‘Curly’, was busy collecting fares. Navy Officers and businessmen chatted together sharing the day’s events, or read a newspaper while enjoying a pipe or cigarette.

Jones looked up momentarily and glanced out the saloon’s port-side windows. He caught his breath. His attention was instantly captured by a large ship, barely 100 yards away, heading straight towards them. Judging by her large creaming bow wave, she was moving at a considerable speed.

Immediately recognising the danger, he ordered the startled men around him to get out, then ran for his two mates in the engine room.

Taken aback by this unexpected interjection, passengers hurried over to the ferry’s port side and could not believe what they saw. Their eyes widened in horror as they saw a passenger liner over three times the ferry’s size, almost upon them. Her sharp steel bow was already abreast of Greycliffe‘s funnel, and barely three or four feet from of the aft gangway.

Businessman Erik Dahlen sat in the stern of the upper deck, facing aft. He glanced up momentarily as he turned a page of his newspaper and was startled to see huge liner almost on top of them.

He heard shouts from below, when, almost simultaneously, the deafening roar of the big ship’s horn abruptly shattered the idyllic scene. Heads whipped around as a second thunderous blast exploded from the liner’s horn. Startled by it’s close proximity, passengers were even more horrified to see the tall steel bow of a large ship towering over them, higher than the ferry’s upper deck.

Passengers jumped up in fright and ran in panic to wherever they felt would be safer. Pandemonium broke out as schoolgirls screamed and mothers instinctively snatched up their children. There was little time to think; people ran in every direction in a vain effort to escape the tons of steel bearing down on them.

Incredibly, up in the ferry’s forward wheelhouse, Captain Barnes had, until that moment, been completely unaware of Tahiti’s presence. The sudden, unexpected snarl of the two horn blasts so near made him jump. He spun around to look aft through the starboard wheelhouse window, but saw nothing.

Stepping across to the port side window, he peered out. To his shock, he saw Tahiti’s bow just feet from the ferry’s side. Clearly too late to avoid the inevitable, he instinctively sprang for the wheel and swung it hard to starboard with all his strength. With a dull thud, the liner’s bow struck the ferry by the aft gangway. The little ferry had not even had time to react to her Captain’s helm.

At first, it seemed Tahiti would simply push Greycliffe aside, but within seconds the ferry’s bow wheeled around until she lay perpendicular to Tahiti’s course. Accompanied by the screams of her panicking passengers, the surge of liner’s bow wave thrust Greycliffe through the water ahead of her, pushing the ferry over enough to submerge her starboard rail and put several feet of water over the main deck.

As she listed, Stan Whalley climbed up over the ferry’s port railing and crawled forward, along the outside of the vessel. As he passed the gangway, he glanced down momentarily at the panic-stricken faces of those fighting to escape the cabins “an image which haunted him all his remaining days” then he continued forward until he reached the bow propeller.

John Corby, on the upper deck, dashed for lifebelts for his wife and daughter. Balancing awkwardly, he turned to see them for a split second holding hands at the top of the stairs. Then Greycliffe rolled over and they were gone.

With the sickening creak-and-snap of splintering timber, Tahiti’s sharp steel bow burst through the wooden ferry like an axe, and split her in two. The decks of the Greycliffe came tumbling down and passengers were flung in all directions, recounted one witness. Barely faltering, the momentum of the 8000-ton liner carried her on through the debris, portions of the ferry passing down each side.

Terrified passengers in the saloons fought to escape, thrashing desperately against the force of seawater as it burst in towards them. Those on deck were sucked deep into the underwater darkness as the ferry’s broken body sank to the bottom.

Cold water found Greycliffe‘s furnaces. With a roar, the bow heaved as the boiler imploded. With a gush, a great cloud of steam shot into the air, intermingled with flying pieces of timber. Water boiled and hissed as it closed over the ferry’s pitiful remains.

Stan Whalley held onto the bow near the forward propeller as the ferry sank. He went all the way down with her and felt her hit the bottom. Although holding his breath, he found his chest expanding and contracting from the water pressure. It tore muscles in his chest and he wanted to scream in pain. Panicking, the non-swimmer fought and kicked upwards. His leg numb from a blow he could not remember, he shot to the surface.

Initially knocked unconscious by the impact, 14-year-old John Carr was quickly brought around by the cold harbour water, and swam for his life. Schoolgirl Gene Wise opened her eyes under water only to see Tahiti‘s propeller coming straight for her, but swam out of its path before it whooshed by.

Erik Dahlen broke the surface gasping for air. Finding nothing to cling to, he sank again, but then, surfacing a second time, he came upon a lifebelt and grabbed it to support himself. Exhausted, he hung on with all his strength.

Ken Horler found his leg tangled in rope as he reached the surface and was dragged down again. Thinking he would not survive, a vision of his mother’s face appeared before him. Then, in the next moment, he disentangled himself. Choking on mouthfuls of salt water, he burst out into the fresh air, gasping, coughing, and bleeding from cuts.

To his horror, John Corby found himself in the water surrounded by bodies as they rose to the surface. He frantically searched for his wife and daughter, but could not find them.

All around him was chaos. The water was alive with dozens of bobbing heads, spluttering and screaming, hands groping for anything to keep them above water. Surrounded by the remnants of what moments ago was a perfectly stable Sydney ferry, Ken Horler clambered to safety atop what he later discovered was one of the two wheelhouses, and helped others aboard.

At this moment, the Water Police launch Cambria rounded Bradleys Head, travelling towards Circular Quay, on routine patrol. Sergeant William Shakespeare, in command of the vessel, could hardly believe the unexpected sight that lay before him. He increased speed and raced to the scene, immediately ordering constables George Day ( possibly Regd # Q 9219 ) and Ernest Maguire ( possibly Regd # Q ???? ) into the water.

Passing ferries and all manner of other vessels rushed to the scene. The Pilot Steamer Captain Cook II was dispatched from Watsons Bay; the Sydney Harbour Trust’s steam yacht Lady Hopetoun hurried over; the ferry Kummulla, which had just landed passengers at Taronga Zoo, immediately turned back; the tug Bimbi rushed over from near Garden Island and the Naval Launch Sapphire diverted from its course as soon as it saw the commotion.

The ferry Woollahra turned from near Fort Denison and raced back to lower her lifeboats. As she arrived at the scene, a man sprang from her deck to rescued an exhausted woman floundering in the water. Then shouts from passengers drew the crew’s attention to a person floating just below the surface. Two men dived in and brought an unconscious woman aboard, where she was eventually resuscitated.

Greycliffe’s Captain Barnes was found clinging to a raft and was taken aboard the ferry Kurraba. He soon recovered sufficiently to return in a lifeboat to help rescue others.

Woollahra’s boats later brought seven survivors ashore, including Captain Barnes, but they also brought in two severely disfigured bodies. Bimbi retrieved twelve survivors and a body from the water, whilst Sapphire was able to rescue another dozen. The Police launch, Cambria, rescued eleven more and found the body of James Treadgold.

Many of the surviving passengers and the bodies of those who had died were taken to the Man’o’War Steps, on the eastern side of the Fort Macquarie Tram Depot. It became a temporary casualty clearing station where men of the Central District Ambulance Service treated the injured, with the assistance of the Police, civilians and workers from the depot.

As the news broke, streams of anxious friends and relatives arrived at Bennelong Point. Several hundred onlookers also lined the waterfront, hampering the work of medical personnel and the police.

The dead were laid out on the pathway by the Man o’ War Steps, where police prepared them to be taken to the City Morgue for identification. Meanwhile, a relay of ambulances rushed the injured up Macquarie Street to Sydney Hospital and returned for more.

Distraught relatives also gathered at the morgue seeking news of missing family. To their horror, many soon found themselves standing before the body of a husband or a wife ”even worse a child” to identify them for the authorities.

On the harbour, passengers on passing ferries jostled for the best view of the accident scene in the fading dusk light. The water was littered with debris, and no-one could believe so much wreckage had come from one small ferry.

Broken roof racks, still containing lifebelts, gave grave testimony to the swiftness of the accident. Barely distinguishable, the aft wheelhouse drifted aimlessly with the tide. Here, amongst the mess of seats and broken wood, a handbag was seen, there a briefcase. A child’s doll. A businessman’s hat.

As night fell, many were still feared missing. In the twilight, Captain Carter and the men of the Harbour Trust Fire Brigade, aboard the fire tug Pluvius, continued the search by spotlight until well after 8.00 p.m. They were unable to recover any further bodies, but great amounts of wreckage were taken aboard to clear the harbour’s shipping lanes. Overnight, the accident site was marked with a green buoy carrying a red flag and flashing light.

The following morning, Sydney’s newspapers were filled with stories of the disaster. Every paragraph was headlined with an emotional eye-catcher: ‘Appalling Harbour Disaster’ – ‘Caught in Wreckage’ – ‘Sisters Killed’ – ‘Piteous Scenes’ – ‘Missing Man’ – ‘Wife and Daughter Lost’ – ‘Crushed to Pieces’ – ‘Heartrending Scenes’ – ‘Great Confusion’.

The Sydney Morning Herald reported that the bodies of eleven people had been recovered. Twenty-six were reported missing and more than 50 had been injured and treated in hospital. Special editions gave readers updated casualty lists and the latest details.

The unenvious task of recovering those who did not survive was undertaken by Harbour Trust divers Thomas Carr and William Harris. The day after the accident they were lowered to the wreck, lying in about twenty metres of water, and cut their way inside.

It was dangerous work and only slender ropes and thin air lines attached them to a pontoon on the surface. Carr and Harris worked in 2-hour shifts, supplied with air by four men constantly employed in turning the wheels of the air pumps.

The two divers used hacksaws to remove decking which was impeding their search or endangering their safety. Occasionally, there were tense moments when large portions of decking broke away and shot to the surface, threatening their lines. It was distressing work, and considered one of the most terrible tasks performed in connection to the tragedy.

That first day, thirteen bodies were recovered. Amongst them were Surgeon Lieut.-Commander Paradice, Dr. Charles Reid, and architect Alfred Barker, who were found in the smoking saloon. The body of high school teacher Reginald Wright was recovered, and Mary Corby was found with her young daughter held firmly in her arms. Three others were found with no obvious wounds; sadly they had simply been pinned down by lengths of twisted metal.

Under drizzling rain the bodies were brought to the surface and taken aboard the lighter Delilah. Ferries passing the scene of the accident lowered their flags to half-mast.

Several days later, Sydney’s Lord Mayor, Alderman John Mostyn, convened a meeting at the Sydney Town Hall to open the ‘Greycliffe Disaster Relief Fund’ for the relatives of the victims. He announced the receipt of three donations to start the fund, £50 from Amelia Marshall of Waverley, £1 1s from L. H. Gray of Moore Park Pharmacy, and £1 1s from Sydney Boys’ High School student Frank Little.

Within days, contributions to the relief fund had risen to £986 11s, helped by a £15 donation from the Japanese Club of Mosman. The honorary treasurer of the fund was Edmund Horler, Town Clerk of Vaucluse, and father of accident survivor, 14-year-old Ken Horler. Others members of the committee were Aldermen A. Charles Samuel, George Hooper, and Harry A. J. Abbott.

Meanwhile the recovery of bodies continued. On 10 November, the body of Charles Garrett floated to the surface with two other bodies when a part of the ferry’s hull was moved during salvage work. The two others were identified as those of 11-year-old schoolboy, Bernard Landers, and 70-year-old retired gardener, William Jones, who was identified by an electricity bill he carried.

The following day, four more bodies were recovered when they, too, floated to the surface around the wreck site. They were subsequently identified as dockyard workers William Barry and Frank Hedges, the latter of whom had a handkerchief in his pocket embossed with the initials ‘FH’, Prisons Medical Officer Doctor Robert Lee-Brown, patron of the Moore Park Golf Club, and retired Master Mariner Captain John Ragg, who was identified by a receipt in his name which was found on him.

Later that same afternoon, diver Harris located the body of 15-year-old schoolgirl Betty Sharp. Moving into a part of the hull which had previously not been searched, he was startled when the form of a young girl appeared out of the darkness. His light revealed the pitiful figure standing upright with outstretched arms, her clothes in shreds; one of her feet was caught in some twisted steel.

By that evening, eight days since the accident, the death toll stood at 35, whilst five remained listed as missing.

On Sunday, 13 November, another two bodies were found floating near the accident site. They were recovered by the Water Police and delivered to the Morgue where they were identified as 37-year-old dockyard worker John Carroll, who was found wearing his Returned Serviceman’s Badge, and 56-year-old spinster Eliza Asher. The search continued for the remaining three people assumed to have been on board.

In a letter to the Editor of the Sydney Morning Herald on 17 November, survivor John Corby, who lost both his wife and only child in the accident, wrote from his home near Moree on behalf of himself, his parents and his parents-in-law. He expressed his gratitude to the city of Sydney for it’s kindness, in particular that of the Police Department and the Harbours and Rivers Department.

On 24 November, another two bodies were located in the wreck, but only one of them could be recovered and taken to the morgue. The well-decomposed body had spent three weeks underwater and the pocket knife and coins found in it’s pockets offered few clues to it’s identity. Some letters were also found but the ink had run and they were no longer legible. Nonetheless, as only three people were still listed as missing, the body was soon identified as that of 58-year-old Navy Engineer Edwin Conner of Watsons Bay, who had boarded Greycliffe at Garden Island. He was buried in South Head Cemetery the following day.

The second body, found wedged between wooden planks, could not be retrieved until a day later. One of only two still listed as missing, the extraordinary amount of gold and gem-encrusted jewellery found upon the body quickly confirmed it’s identity as 59-year-old German immigrant Eugen Wolff of Vaucluse. He was buried at South Head Cemetery on Saturday, 26 November.

Later that day, in an unusual and unexpected twist, the remaining person on the list of the missing turned up alive when he walked into the Water Police station and assured police he was not on board.

Arthur Hardy was believed to have been amongst Greycliffe‘s passengers as his attaché case and papers belonging to him were found floating in the water amongst the wreckage of the ferry on 3 November.

He explained he had in fact been on board when Greycliffe was berthed at Circular Quay, awaiting a friend. However, when he failed to appear before departure, Hardy jumped off again, just as the gangway was being hauled aboard. In his haste, he left his attaché case behind, and naturally, when it was found in the water after the accident, he was assumed to be amongst the victims.

That same evening he had left for the country and was completely unaware divers were searching for his body. When he returned to Sydney on 26 November, he was surprised to hear he was ‘missing’, and immediately reported to the Water Police to set the record straight.

Police now believed all the victims of the tragedy had been found, but nonetheless maintained patrols in the area of the wreck site for a short time in case bodies of people not reported as missing floated to the surface. Indeed no further bodies were recovered and the official death toll was finally set at 40.

The victims of the accident ranged widely in age; some were retired, some at the peak of their careers, others in the prime of their youth. The communities of Vaucluse and Watsons Bay were devastated, whilst towns further a field also grieved. Lives and perceptions changed forever and the effect on individuals, families and their communities as a whole should not be underestimated. Many a family lost their breadwinner and were forced to cope with new-found financial difficulties.

Families mourned their losses and suffered them in ensuing years. Though the physical wounds of the injured healed with time, survivors carried emotional scars and relived the nightmare of fighting for the surface as the ferry sank. In some cases, the emotional strain also cost jobs.

In 1927, the ‘Greycliffe Disaster Relief Fund’ was set up to help them. By the time it was wound up in March 1931, £6281 had been raised through donations, complemented by an additional £536 earned in interest. Thirty-three people received amounts of between £3 and £110 each to buy clothing or cover funeral costs, whilst a further ten widows received assistance ranging from £275 to £878, according to their circumstances and dependants.

Besides several archived documents, a handful of photographs, and a short silent film clip held by ScreenSound Australia, relics of the tragedy are few.

Greycliffe‘s engines were salvaged from the harbour bed and sold to the Tirau Dairy Factory in New Zealand. They were acquired by the Museum of Transport, Technology and Social History (MOTAT) in Auckland in 1964, and are still there on display today.

The rest of the vessel, however, was broken up and discarded. Over a two-week period in April 1928, Harbour Trust divers used explosives to destroy the ferry’s remains, her funnel being one of the first things to be demolished.

In all, nine bravery awards were presented by the Royal Shipwreck Relief and Humane Society for rescues made by individuals during the accident. These included two Silver Medals, three Bronze Medals and four Certificates of Merit. In 1928 and 1929 awards were made to four of Greycliffe‘s passengers, one of Greycliffe‘s crew, one of Tahiti‘s crew, one of Woollahra‘s passengers, and two Water Police Officers. In September 1928, Water Police Sergeant William Shakespeare, who had recently died, was also commended posthumously for his role in rescuing Greycliffe‘s passengers.

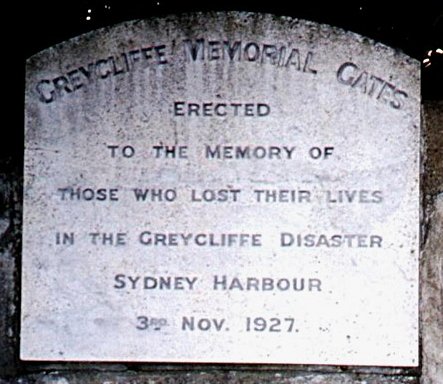

In memory of the accident’s victims, the ‘Greycliffe Memorial Gates’ to St. Peter’s Church in Watsons Bay were unveiled by the Right Reverend Bishop D’Arcy Irvine on 11 May 1929. The original gates, made of timber, no longer exist, but plaques to their memory can still be seen today on either side of the entrance.

Police Officers Involved in the Rescue.

DAY, George Frederick, 48.

-

Police Constable with the Water Police

-

Aboard Police Launch Cambria, one of the first to attend the accident on 3 November 1927; recovered several survivors and bodies from the harbour

-

Statement of evidence given at the Coronial Inquest on 10 January 1928, SRNSW 2/10498, pages 122-124

-

Awarded a Bronze Medal by the Royal Shipwreck Relief and Humane Society of N.S.W. in September 1928 for his rescue efforts

LAVELLE, Anthony

-

Detective Sergeant with the Water Police

-

Gave evidence regarding the death of one of Greycliffe’s initial survivors at the Coronial Inquest on 7 February 1928, SRNSW 2/10498, page 695

MAGUIRE, Ernest Norbert

-

Police Constable with the Water Police

-

Aboard Police Launch Cambria, one of the first to attend the accident on 3 November 1927; recovered several survivors and bodies from the harbour

-

Statement of evidence given at the Coronial Inquest on 10 January 1928, SRNSW 2/10498, pages 109-111

-

Awarded a Bronze Medal by the Royal Shipwreck Relief and Humane Society of N.S.W. in September 1928 for his rescue efforts

SHAKESPEARE, William, Sergeant, 53

-

First Class Police Sergeant, based at the Sydney Water Police Station

-

Harbour and River Master, Certificate No. 876, issued N.S.W. 19 March 1904

-

Skipper of the Water Police Launch Cambria; one of the first to attend the accident on 3 November 1927; recovered several survivors and bodies from the harbour

-

Front page picture printed in the Daily Telegraph News Pictorial, 5 November 1927

-

Statement of evidence given at the Coronial Inquest, SRNSW 2/10498, pages 7, 8 and 45

-

Joined the Police Force in 1900; died 24 May 1928, though unrelated to the Tahiti-Greycliffe Disaster

-

Posthumously commended by the Royal Shipwreck Relief and Humane Society of N.S.W. in August 1928 for his rescue efforts

The above information was researched by Steve Brew from Sydney, and no doubt has taken many hours of reading and digging through the NSW State Archives at Kingswood, and studying the newspapers from the year of this disaster, please bear in mind that every statement and every occurrence mentioned in the text is factual and as it occurred.

The above is only a condensed version, Steve has a full manuscript, which includes biographies of the victims, passengers and crews, now numbers over 330 A4 pages, if you would like to contact Steve for any further information regarding the 1927 Tahiti-Greycliffe story, please feel free to E-mail him on brew@clients.ch .

UPDATE: 15 October 2003

After many years of hard work, Steve Brew will launch his book on the 6 December 2003 at the Australian National Maritime Museum at Darling Harbour. The book is called ‘Greycliffe; Stolen Lives” and is well worth reading. For information regarding Steve’s new book please visit his site by clicking here.

“Greycliffe; Stolen Lives” is available on the shelves of the Justice and Police Museum, Corner of Albert and Phillip Streets, Sydney NSW 2000, Telephone 02-9252-1144, E-mail: davido@hpb.hht.nsw.gov.au . This book is well worth reading and will give everyone a better understanding of what happened on that fateful day in 1927 that became part of Australia’s History.